The End of Aquatic Invasive Species in the Great Lakes

Fall 2020

The End of Aquatic Invasive Species in the Great Lakes

By Casey Merkle

The End of Aquatic Invasive Species in the Great Lakes

By Casey Merkle

Introduction

Conflicts, confrontations, and resolutions are normal… a part of life. As much a part of life as it is to breathe. Breathe in, I share an opinion on one hand, breathe out, I share a conflicting opinion… in the same breath. In between the in and out is where I really start to liquify what I thought at one time is not so simple, and that I must consider taking another breath.

Which do you prefer, the lake or the ocean? Depends on the place. Maybe, it depends on the how much that place feels most like a home.

My home was in a northwest suburb of Chicago, called Barrington. Today, when the word Barrington comes out of my mouth, I immediately feel a repulsion. Its mouth feel brings visions of teens in their hummer vehicles pulled by white, shining horses off to the prom. Moving to Rhode Island, I started to visit and then work in Barrington, RI which was more or less the same but this time Teslas and Jeeps packed into parking spaces like glimmering jules organized behind the gas station counter. Both offer a tempting illusion.

Where I grew up, there was a shallow pond with splatterings of duckweed in the summer, and frozen ice bubbles dotting the surface like a million moons in the winter. We called it Tower Lakes and kids ran around barefoot through private yards to the beach, never missing a day of sunshine.

Invasive species were not on the mind of 10 year old me. Not until, when climbing around the shoreline over submerged rocks I got a razor slice in the bottom of your foot from a little bivalve called the zebra mussel. Then, for a brief moment, they are a nuisance but I wouldn’t go as far to say they had to be removed. As a child, you learn these lessons. And, one of them from that experience was that water shoes are never a bad idea along a rocky shore.

From Tower Lakes, I was fortunate that Lake Michigan was only a short train ride away. I didn’t stray too far from home and moved to the city after college to work at Lincoln Park Zoo. Every morning at 7am, I’d grab a granola bar and hustle my way along Chicago’s lakefront, fighting the strong winds that ripped past my face.Winter forced me into a 50-passenger packed bus avoiding that cold lake wind which would shock your bones and numb your hearing. The sight of Lake Michigan as I stepped off the bus and turned to cross the street was enough to energize me for the day. Even if it did bring tears to my eyes. Not from the icy winds, but from joy, anger, and sadness. Lake Michigan could make me smile, cry, scream and laugh in the same breath..Was it that I was in bewilderment and my brain just couldn't pick one emotion to settle on?

Do I prefer the lake or the ocean? I can’t decide because they both carry a deep, lonely, and mysterious past, present and future. To understand me and why I have this attachment to the Great Lakes, a good example would be to examine my closet. On a hanger in the back, you will find myGreat Lakes sweatshirt that is covered in shipwrecks along with their date, coordinates (or none if they never recovered the ship), and the number of people perished. It’s a lake with magnificent stories and only she knows how they end. That’s deep.

On the note of loneliness, I can relate to Lake Michigan. When I feel a sense of loneliness and emptiness, it settles when I stare out at the horizon of the lake thinking of the number of people who have been along this shore and uttered the same thought for generations.

Tied up with all these feelings are the mysteries of the Great Lakes. They’re not called Great for no reason. Tens of millions of Americans rely on the fresh water for drinking, sustenance, work, and recreation. Out of the world’s supply of surface fresh water, the Great Lakes hold 20 percent. The great mystery is why are they dying? Why does a part of the country with so many resources, and with so much to lose, not reach a resolution and imagine what a deeper, reciprocal relationship with the Great Lakes would look like?

Facing the Great Lakes

When I ask myself, do I prefer the lake or the ocean? To me, I can’t decide because they both carry a deep, lonely, and mysterious past, present and future. No one understands me and my Great Lakes sweatshirt that is covered in shipwrecks with their date, coordinates (or none where they never recovered the ship), and the number of people dead. People ask me why do I like the Great Lakes so much? Because, I related to them. I, too, feel a sense of loneliness and emptiness at times. It will become clearer as to how the Great Lakes and I share these feelings. I believe it has something to do with semiosis, a system of meaningful signs. Language is more than the audible communication carried out by humans; it encompasses the complexities of intersubjective and interspecies dialogue, involving nature and humanity (Gagliano 2017). The Great Lakes, as an entity, has a system of meaningful signs that over time, humans have learned and passed down through generations. Those signs mirror a reaction in myself. This is the Great Lakes call for help, to be set free of its suffering.

Tens of millions of Americans rely on the fresh water for drinking, sustenance, work, and recreation. Out of the world’s supply of surface fresh water, the Great Lakes hold 20 percent. The Great Lakes and humans share an extricable relationship, at least, through a dependence on drinking water for 30 million people. A Greatrelationship with the Great Lakes, should be a two-way street. But, from the perspective of the Great Lakes, I’m sure the last two centuries has felt more like a one-way street. Geologically speaking, the Great Lakes has not even batted an eye at this blip of suffering.

Who am I to the Great Lakes?

Living in naturecultures means developing a self-reflexivity, continually wrestling with the interconnections of natures and culture, politics and science, the humanities and the sciences, and feminisms and science (Subramaniam 2001). I self-reflect on research I conducted my senior year on an aquatic invasive species (AIS) in the Great Lakes. To supplement my reflection and lessons, I will examine other cases of AIS as well, including zebra mussels, the round goby, the Great Lakes sea lamprey, and Asian carp. I will attempt an imaginative reconstruction of the spiny water flea and outcomes of my research. I, as the human actor performed scientific work in relation to many objects and subjects of study. Following Banu Subramanian’s inspiration from Italo Calvino, I will approach this essay as a mental exercise of undoing my disciplining. This is important because my practice was learned under a patriarchal and strict rule of western scientific epistemology. My focus was on the AIS, but I want to reject that narrow vision to expand outward peering into the ethos, the lifeworld, the umwelt (Von Uexküll 1934) of the Great Lakes. This will help relate my studies to people, multi-species, politics, art, global trade, money, and all things that become-with the Great Lakes.

I will situate myself back onto the boat in Green Bay, Lake Michigan and recreate a map of my knowledges and methodologies. I recognize that I learned a particular and refined method of classifying, analyzing, and scientific writing. This will challenge me as I will have to turn the gears back and begin writing a new narrative challenging my own studies and the approach to raising public awareness of AIS, as well as posing the question that no aquatic ecologist, or policy maker, studying the Great Lakes wants to answer… is it time to give up on preventing the spread of AIS? Who is really behind the degradation of the Great Lakes? Who or whom is the invasive species?

How I landed in the Great Lakes

In 2016 and 2017, a pattern of unexpected events led me to captain my own small ship… as I called it. In reality, it was a small university-owned skipper boat I pretended that I could take off in that boat anytime. I’d leave all my studies behind and let Lake Michigan be my teacher. I was a student researcher in an aquatic ecology lab studying the impacts of AIS on the Fox River and Green Bay ecosystem which is part of the long-outstretched arm of water separated by the Door County peninsula in Lake Michigan. It is also known as Death’s Door due to the unpredictable currents, capsizing small skippers.

The summer of 2016 was a scorcher. I was 20 years old living in a small dorm on campus with no air conditioning and a cup of noodles, a bag of potatoes, and carrots dipped in peanut butterFor one week, we lost power to the dorms and I slept in the lab. The lab was my escape from outside where the sidewalks could cook a full egg and sausage breakfast. My time was split either in the lab or on the windy shores of Green Bay with our research boat, The Daphnia.

My lab mates were exceptional and are some of my best friends to this day. Four women striking down any misogynistic comments on our abilities, like backing up the boat or wondering what women were doing headed out to choppy waters by ourselves lugging heavy research supplies back and forth from the van.

Long days were spent collecting samples of fish, invertebrates, zooplankton, algae and measuring biodiversity. The Fox River is an important route that allows for cargo ships to dock in Green Bay, WI. As we were going out to collect samples, one large cargo ship passed us. I could feel the vibrations of this obscene object move through our small boat out through my fingertips. I was unsettled, watching the large ship go through the shallow canal.

Because my true loves during college were The Daphnia and Lake Michigan, I developed a research study on a subject that would require me to take her out on the water for another summer. My subject was a type of aquatic invasive species (AIS) called the spiny water flea, a relatively large zooplankton that has a long spiny tail. At the time, my professor was asked to monitor their population in Green Bay and to note any interesting findings. I’d head out into the choppy waters of Green Bay and toss our zooplankton net out behind the boat to tow along collecting little water fleas. I began to notice that the color, texture, and viscosity of the water would change from day to day. How were water quality and zooplankton ecology connected? How had the introduction of the spiny water flea in Green Bay affected the viscosity of algae in the water? What tiny organisms were intertwining to create that gelatinous, stringy green saliva in the water?

These questions guided me to understand how the spiny water flea shifted competition between predator and prey relationships that resulted in visible and cultural changes to the ecosystem. Though it would seem these changes happen under the surface, there is an entanglement of species, fisherman, chemicals, water quality, politics, morph our conceptions of political, economic and cultural contexts. However, this naive version of myself was certain that the spiny water flea was the main actor responsible for the negative impacts on Green Bay’s ecosystem.

Certainty encourages looking from far away. Certainty leads to a closed door. I needed uncertainty to float between the breathing in and the breathing out. What I lacked in my certainty was the history of Green Bay. More context to describe what happened leading up to the establishment of the spiny water flea in Green Bay would help understand why they were there in the first place. There were more factors at play in this natureculture story that I had yet to uncover.

Speaking of Natureculture

Nature and culture, are co-constituted, entangled processes of semiotic as well as material. An analysis of my past research and multiple AIS stories, emerges a history of “naturecultures”, tracing and elaborating the inextricable interconnections between natures and cultures (Subramaniam 2001). What I am trying to understand about AIS is hidden underwater, above ground, and within the subterranean of the Great Lakes. Habitat, biodiversity, history, geology, science, politics all becoming-with this “natureculture” story.

Through this essay, I will tell stories of AIS that are important to understand in the inextricable connection between nature and culture of the Great Lakes. My goal is not to ignore the spread of AIS, but to reimagine their significance and deconstruct the fear around AIS. To what extent is aquatic invasive species (AIS) management necessary? How has the spiny water flea (discourse) shaped politics and culture of the Great Lakes?

Socio-ecological Thinking

First, I should take a deep breath and remind myself of the definitions pertinent to this story. The term ecology has gone through many definitions since the 1800s. “Ecology” was coined by the German zoologist Erns Heakel in 1866. It was generally defined as organized knowledge about a vast array of relationships among species and their environments. Reading from Keywords for Environmental Studies, I understand ecology as the observation of interrelationships with and within organisms, ecosystems, and human culture which not only shape the natural world but also shape situated knowledges of our present and future of humanity. Ecology as I approach my thinking, involves the environmental and social sciences working together (Seidler, 2016).

A Brief History of The Great Lakes

Geology

For a long period of time, humans have caused habitat destruction on the Great Lakes. Impacts have risen due to industrialization and globalization, and are a result of physical, chemical, and biological changes to the environment leading to species extinction, habitat pollution, habitat loss, and non-indigenous species introductions. Before humans, the origin of the watershed is a product of multiple glaciations during the late Cenozoic as well as redirected drainage, particularly during retreat of the last ice sheet.

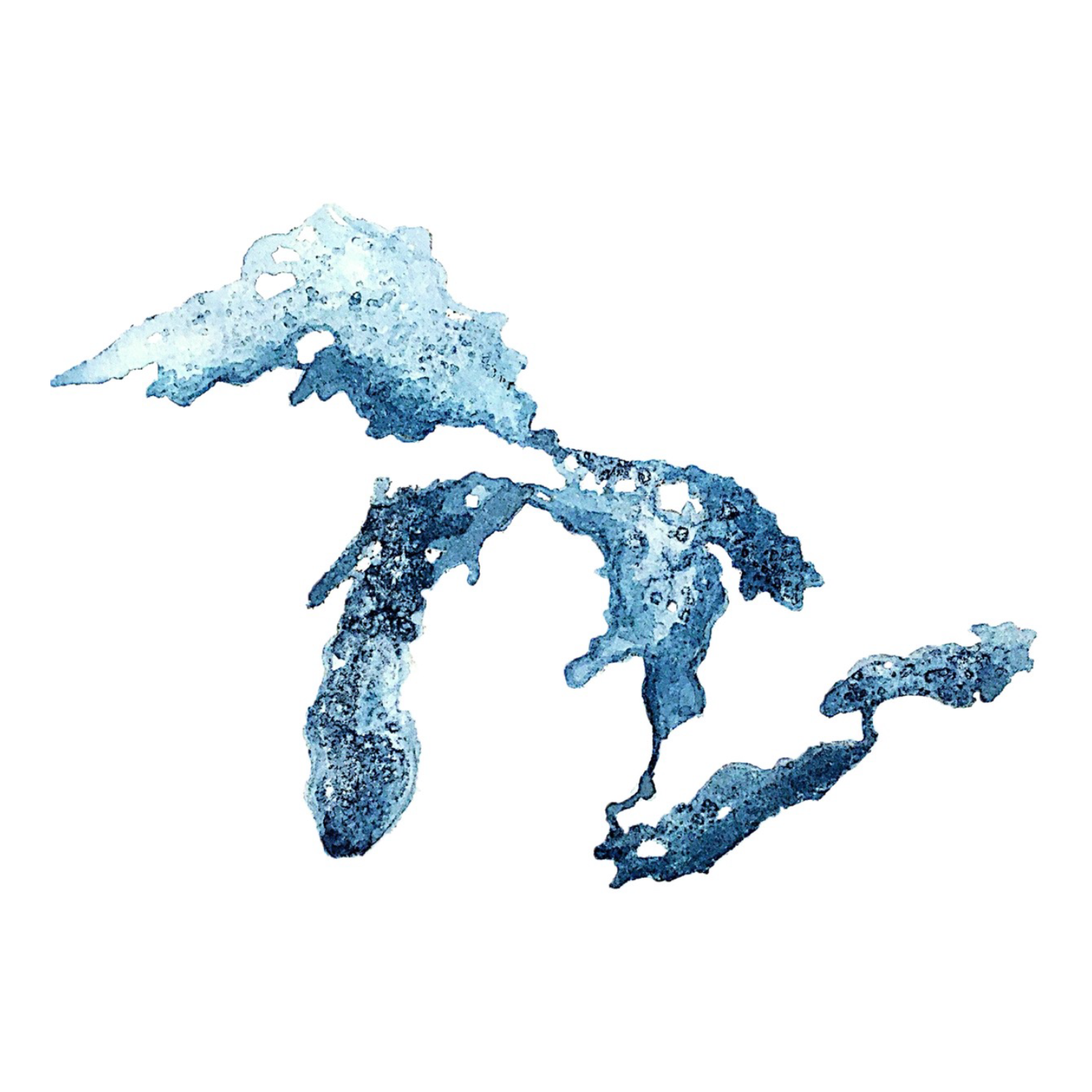

As fate would have it, in the geological becoming of the land separated the water into the five Great Lakes, Erie, Huron, Michigan, Ontario, and Superior. At one point, the water flowed through them as one on the surface, but scouring of the rock created deep depressions for the five Great Lakes to become what they are today. Though they are called the Five Great Lakes, the water is always flowing between them down a slow-moving river west to east.

The Niagara Falls cascade from Lake Erie into the waters of Lake Ontario below. It is estimated that in 50,000 years the falls will disappear and with it the cliffs that have separated the upper Great Lakes from the Eastern Seaboard. The slow-moving river will become fast, creating a new geological landscape through forceful erosion. Eventually, the once Great Lakes will lower until it meets sea level Though that future is far away, it does beg me to imagine how that change begins to shift the midwestern landscape. All those dairy farms, corn and soybean fields, would surely drown in wetness, as these floodplains continue to expand.

People

The land was covered in dense impenetrable forest and was navigable only by canoe. Residing in the region for many generations prior to settlers, were the Miami (also called Maumee). The language spoken in the Great Lakes region was Algonquin, and other First Nations resided in the region, including Ojibwa, Ottawa, Menominee, and Potawatomi). French traders and explorers were the first Europeans to arrive in the Great Lakes region between 1550-1600. The king of France sent them to chart the river systems as highways facilitating access into the interior of North America. The Great Lakes include, Lake Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie, and Ontario. They hold over 5,400 cubic miles of water – therefore accounts for 21% of the world’s surface freshwater. These inland freshwater seas, provide water for drinking, shipping, power (electrically and conceptually), recreation, aquatic life, agriculture, and more. North America relies on the Great Lakes for 84% of their surface fresh water.

Ecological Economics

The Great Lakes are an ecological economy, with natural capital in water supply, climate regulation, habitat for species, food, recreation, transportation, and cultural amenities. Economy is not independent from ecology, or the natural world. Rather, it is an ongoing effort that integrates the study of what is desirable to what is sustainable on our finite planet (Costanza 2016). That is why I describe here the transdisciplinary field that integrates humans and the rest of nature as ecological economics (Costanza 1991; Costanza et al. 1997; Daly and Farley 2004; Costanza 2016). Integrated with social and cultural capital, the Great Lakes provide a hub where natureculture connections forge through social networks, cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, trust, and sense of belonging.

Becoming-with Global Trade

There are five ports in the United States, including Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Duluth, and Milwaukee. Canada’s major ports: Toledo, Port Colborne, and Toronto. Coined an Economic Powerhouse, coastal areas represent strong economic and ecological engines in the Great Lakes. For every dollar spent in Great Lakes Restoration Initiative funding, an estimated $3.35 in economic activity is produced. A total of $3.1 trillion gross domestic product, employs 25.8 million people, supports $1.3 trillion in wages and contributes to this developed economy. This shipping system is called the Great Lakes/St. Lawrence Seaway . The story of the Seaway is quite dramatic. It was one of those ideas where you look back and wonder how nobody foresaw this becoming a nightmare? But, during the 1950s when the Seaway was constructed, the race for control over industry and shipping was well underway. Global, national, as well as regional competition drove the opening of the Seaway. At one point, the Seaway’s oversea shipping peaked at 23.1 million tons per year in 1970. Why the Seaway was constructed is complicated. One major reason was to increase exports to foreign countries. It was the gateway to the rest of the world and every Great Lakes coastal city wanted a piece. It was about expanding power, capital, and control. At the time, Chicagoans had a “second-city complex” that they wanted to subside. Having access to a port out to sea would allow them to compete for the “first-city” beating NYC. As I’ve learned, humans are prone to mistakes. After great costs were expended to build the Seaway, which included flooding large towns and people being forced to move within a one-year notice, it barely makes a dent to match the shipping pace of trains and trucks. Now, less than 5% of the Great Lakes shipping industry is overseas. Duluth paid millions for the construction of a special shipping crane in hopes of enticing shipping container imports. It has remained idle for 20 years! A large part of this shortfall was that the Seaway is covered in ice over the winter and has a shorter shipping season compared to ground shipping. The Great Lakes coastal cities wanted to increase their capital through exports. In their struggle for power, they also invited aquatic invasive species into their ports. But I’m careful not to point the finger at foreign imports to be at fault for this. When I trace to the origins of this project, it was the United States and Canada that funded the Seaway.

Aquatic Invasive Species and the Great Lakes

Since the Seaway was opened in 1959, it has acted as a corridor for aquatic species to traverse. This e journey isn’t on their own. They are trapped in up to six million gallons of ballast water, which is used to maintain balance of a ship. Once the ballast water is discharged from a ship, any organisms that were picked up at its place of origin are released in exchange for cargo. Within these billions of organisms could be a traveler that is forced to make its home in the freshwater of the Great Lakes. They need to survive in their new home and if they can, they will.

Aquatic Invasive Species (AIS) or Non-Indigenous Species (NIS)

Before discussing several cases of AIS in the Great Lakes, we should pause to define this area of science that I spend most of my time thinking about, called invasion biology. From an aquatic ecologists’ perspective, I prefer to not isolate invasion biology because it is not a separate study but an integrated part of ecology. Rather, I prefer to think about my studies from the standpoint of community ecology. As an aquatic ecologist, I investigate the factors that influence community structure, biodiversity, and the distribution and abundance of species. These human and non-human factors include interactions with the abiotic world and the diverse array of interactions that occur between non-human and human species. Invasion biology is the study of invasive organisms and the processes of species invasion. The USGS describes that biological invasions are the second leading cause of extinction behind habitat destruction. Habitat destruction weakens the integrity of an ecosystem and makes it susceptible to invasive species. Without habitat destruction there would be no open door for species invasion. If humans are the cause of habitat destruction, then the species invasion that seems of significance would be the invasion of humans and its impacts on the planet. My point being, biological invasions cannot be the second leading cause of extinction. Habitat destruction is the umbrella for all other causes of extinction. The point of hierarchy is mute.

The Lake Sturgeon

One of the planet's greatest wonders, there is nothing else like the Great Lakes on earth. Theese lakes sustain a variety of aquatic species, including the endemic Lake Sturgeon. These prehistoric, dinosaur fish, can travel up to 1000 miles. On one of my trips to the Shedd Aquarium in Chicago, I entered the Great Lakes exhibit. They have a touch tank where several of these large sturgeons live. They swim about with their long bodies bumping against the tank. Each time they hit the side of the tank; their massive weight sends reverberations through the floor up into my body. Their skin is shiny, black as the night, and smooth to the touch. When I pressed two fingers against their skin, it felt unlike any other fish. They don’t have scales the way most freshwater fish do. Instead their skin is partly cartilaginous skeleton, so it feels like a slimy balloon stretched thin over pebbly rocks. Lake Sturgeon are now extinct in most of its ancient spawning grounds due to overfishing and pollution. The industrial revolution lead to an appearance of mercury and lead in the Great Lakes. Also, the flushing of raw sewage, dioxins, acid rain, PCBs, and fertilizers into the lakes decreased their population by 99%. By the 1980s things started to improve due to governmental regulations on air and water pollution.

The Bald Eagle and Sea Lamprey

Another species that inhabits the Great Lakes region is the Bald Eagle. Since the pesticide DDT was banned in the 1970’s, this North American bird of prey has made an impressive recovery. Recently, their numbers have started to decline and researchers were perplexed by the sudden dip. Nest monitors found that the Bald Eagles were feeding their young an unusual type of fish, long and slender with a suction disk mouth filled with small sharp, rasping teeth and a file-like tongue (Figure 3). This fish, the Sea Lamprey, uses this tongue to attach to fish, puncture the skin, and drain the fish’s body fluids. They also produce an anticoagulant in their saliva to ensure that the blood of the host fish does not clog while they feed. I’ve never seen a sea lamprey in person, but in pictures, they look not at all appetizing. The chicks of bald eagles cannot digest the sea lampreys. The mothers, unknowingly feed their chicks their last meal. This is the innocence of the species that gives pause to consider the entanglement of species here. The sea lamprey wasn’t always a readily available food source (albeit poison) for bald eagle chicks. They were introduced to the Great Lakes 80 years ago, some purposefully introduced. As the bald eagle is a national symbol, the U.S. funds plenty of research to protect their population. Adult Bald Eagles do, in fact, eat spawning lamprey. DNA data suggests that the sea lampreys may have been living in Lake Ontario for thousands of years. There’s more to the story of sea lampreys and their connection to bald eagles. Researchers have yet to study what the sea lamprey may be ingesting in its habitat that might lead to bald eagle chicks dying. It’s clear that fear of the sea lamprey takes precedent over habitat health. I can understand why people have a fear of this species. They look like the monster from the television series Stranger Things (Figure 4). In this story, the bald eagle and sea lamprey innocently becoming entangled in media, science, politics and death. Is there a happy ending for the bald eagle? Death for sea lampreys at the claws of the mother eagle, life is at stake for the baby chicks. Do researchers stop at the sea lamprey as the responsible one? Empathize with the sea lamprey for a moment. As an innocent species, the sea lamprey, like other lampreys, is food for the bald eagle chicks. Consider the toxin, DDT. It was banned and the eagles made a recovery. What if other trace toxins, such as microplastics, are making their way from the sea lamprey to the baby chicks, leading to death?

![]()

Sea lamprey mouth courtesy of USGS.gov (left) and illustration of Stranger Things monster courtesy of https://formlabs.com/blog/visual-effects-stranger-things-monster-demogorgon/ (right)

The Round Goby and Lake Erie Water Snake

A few other species that have been introduced to the Great Lakes include the round goby, zebra mussels, and Asian carp. The summer after my junior year of college, I spent a portion of my research setting traps for round goby monitoring along the shores of Green Bay, Lake Michigan. They had already started to thrive in most of Lake Michigan, but it was unknown how wide spread they were through Green Bay. In Lake Erie, the round goby established itself – with human assistance – caused population declines of many native fish due to a limitation on nesting sites that the round goby was very good at competing against other fish to win. However, with this new addition to the Great Lakes, sometimes new prey-predator relationships form. Waiting in the crevices of rocks along the shore was the Lake Erie water snake. Historically, this snake ate mudpuppies and native fish. But after the round goby became established, the snake turned its head toward the new neighbor as a food source. Today, the water snake’s diet consists of 90 percent round goby and 10 percent mudpuppies and native fish.

Zebra Mussels

I try not to rank species, but truly, my least favorite of these non-indigenous species (NIS) is the zebra mussel. Mostly, my disdain towards them comes from the repeated pain I felt each time one of these sharp creatures sliced the bottom of my foot. To be fair, I learned to adapt to their presence. Now, I never go in to shallow waters of the Great Lakes without proper footwear. This is especially important when the bottom is rocky. This action is part of my co-habitation with the zebra mussel. In great numbers, the zebra mussel and the quagga mussel, its close cousin, are incredibly efficient filter feeders. They are passive filter feeders, meaning their life is spent attached to a rocky surface with their mouths hanging open to slurp up nutrients all day and all night long. In great numbers, their filtering has led to a shift in the Great Lakes ecology. The food web changes, water becomes clearer, and coat water intake pipes. They haven’t only spread to the United States. They are introduced and established worldwide. The link between humans, water, and zebra mussels is strong. Where there is a human presence, there is more likely presence of zebra mussels. And, they’re connected through the water with which we drink, play, and bathe.

Questioning The Asian Carp

A quite large non-indigenous species, the Asian Carp, are another actor in the Great Lakes that were introduced via the Mississippi river. There is a great amount of governance that has focused on keeping the Asian carp out of the Great Lakes. In 2002, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers completed an electric fish barrier in the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal. The canal connects the Mississippi River drainage basin (via the Illinois River and its tributary the Des Plaines River) to the Great Lakes Waterway (via the Chicago River) and is the “only” navigable aquatic link between these basins.

These attempts are misguided. By focusing on the “only” navigable aquatic link between the basins, they ignore humans as the main vector, or driver, of the spread of non-indigenous species. Blocking off the waterway with an electric fish barrier doesn’t just hurt the Asian carp, but other fish get caught up in this tension between human and carp. At one point, there was concern about the Asian carp that they poisoned the Chicago River, only to find that no Asian carp had come up that far, yet. Or they had already traveled through, off to find a sustaining habitat. The feeding at the bottom of the Chicago river may be subpar and carp don’t like it if it can’t sustain their bottom feeding habits.

Their close cousin, common carp, are abundant through the Great Lakes. First noted in 1931, they’ve been widespread for a long period of time. People used common carp as a food fish in the late 19th century. More recently, angling for common carp has become a popular sport amongst anglers in the United States. Common carp and Asian carp (grass, black, silver, and bighead carp) fill the same niche as bottom feeders. They don’t have a significant biological advantage over the other. That checks off one describing factor of an invasive species, as they are not highly competitive.

The term Asian carp is questionable to say the least. However, I’m not suggesting a name change. It can be described as simple as a non-indigenous species that is named based on where they originate.However, the name finds a place in a culture that is not simple. The name “Asian carp” may not be racist at its core, but the surrounding rhetoric that is used to describe the invasion of “Asian carp” is perpetuating a fear of ‘other’ and by association creates a nationalistica and racially charged fear of ‘other’.I think many scientists and reporters are misguided in their language, which is to play off peoples' fear of the ‘other’.

“Asian carp” is used to describe multiple species of carp, so would it be clearer if we called them by their species name instead of by the group species (i.e. grass carp, black carp, silver carp, and bighead carp)? Or, couldn’t they all fall into the category of common carp? A debate in science communication and journalism exists around the terminology of Asian carp. For example, in The Atlantic a journalist writes, “Asian carp aren’t just offending Midwestern waterways. They’re offending the politically correct.” I think journalists need to be careful when discussing this terminology. The focus isn’t on the naming, but the rhetoric that surrounds it to create fear of the species in question. The argument of The Atlantic journalist is that “These fish are called Asian carp because the species comes from Asia. It’s simple really.” While I agree that the Asian carp is just a carp that came from Asia, the Asian carp is an actor that is part of a broader narrative in invasion biology. This narrative is informed by the acts of desperate scientists and journalists that use fear tactics as a way to alert the public of invasive species. By simplifying the Asian carp to just its name, the journalist ignores the harmful rhetoric that scientists and communicators use to cause concern about the Asian carp’s harmful potential effects on the Great Lakes fishing industry. In fact, the journalist glossed over the explanation for changing the name of Asian carp to invasive carp given by the Democratic state senator from Minnesota, John Hoffman, “Caucasians brought them to America. Should we call them ‘Caucasian carp?’ They have names. Let’s call them what they are.” I believe this point is crucial to the article. It highlights that the root of the problem driving AIS is not the species itself, but that humans degraded the habitat to make it susceptible to invasion, and also acted like a taxi cab for AIS to hail a ride directly into the Great Lakes.

Return to the Spiny Water Flea

Let’s revisit my friend the spiny water flea. We visited various actors that make up the Great Lakes interconnected web of life, including fish, invertebrates, and bird of prey. Now, I will take you deep into the microscopic world of zooplankton and phytoplankton. Break the surface tension of the water, travel down the water column, pass tiny darting water bugs as we go down to through the murky waters until we reach the bottom. At the bottom, we’ll wriggle through the muck where the bottom-feeders dwell. The amount of time I spent on the water to collect samples of these tiny critters affected my world view. I no longer just saw the world by what was in front of me. I could trace the invisible connections that were occurring all around me and through me. The mystery of what is invisible has a strong presence in my life.

Zooplankton Community Ecology

My first publication was called Bythotrephes longimanus in shallow, nearshore waters: Interactions with Leptodora kindtii, impacts on zooplankton, and implications for secondary dispersal from southern Green Bay, Lake Michigan. The spiny water flea, Bythotrephes longimanus, is a predatory zooplankton. They feed on other zooplankton, like the Daphnia. Once established, spiny water fleas alter the food web by eating the same food that Leptodora kindtii, another larger zooplankton feed on. Leptodorais an important food for juvenile fish. When Leptodora populations decline, the juvenile fish struggle. If the puzzle pieces all fit into place, the juvenile fish would be able to feed on both Leptodor and Bythotrephes but the long spiny tail of Bythotrephes makes it unappetizing and difficult to fit in the tiny mouths of juvenile fish. When the juvenile fish populations struggle, fisherman have a problematic season. The implications for secondary dispersal meant that because Bythotrephes was established in shallow waters of Green Bay, all the boats that dock in the marina there could be potential carriers. Bythotrephes could be picked up by a boat motor and carried to an inland lake at the hand of humans.

![A female spiny water flea with four baby spiny water fleas in her sack.]()

A female spiny water flea with four baby spiny water fleas in her sack.

Fox Wolf-River, Paper, and Fishermen

My research on the spiny water flea was situated in Wisconsin’s Fox-Wolf River Basin including Green Bay. Wisconsin’s economy flourished because of its prime location along the Great Lakes waterways which provided access for international and national trade. The Fox-Wolf River Basin was well-known for its industrial and agricultural use. It drains over 15,500 square kilometers (6,000 square miles) and provides transportation routes throughout northeastern Wisconsin (Ball et al. 1985). The watershed includes the largest inland lake in Wisconsin, Lake Winnebago which drains into southern Green Bay via the Fox River. At this connection point, the most severe deterioration of water quality persists. Where the bay meets the river shows extremely low abundance of life indicated by the lack of bottom-dwelling organisms (Balch et al. 1956). Through the 1800’s, industrialization boosted the economy around the Great Lakes and along the Fox River. The lower Fox River provided industrial water supply, commercial shipping, recreational boating, fishing, and swimming. Between 1900 and 1970, the river maintained its industrial and commercial uses, including a booming paper company, foundries, and wastewater treatment plants. These human constructed entities caused pollution that affected the entire watershed. Slowly, recreational activities disappeared due to the river’s poor condition. The pollution from anthropogenic mistreatment traveled downstream and collected into Green Bay, Lake Michigan.

The first noticeable impact by spiny water fleas was on fishermen. The tail spines get hooked on fishing lines and large clumps of them fouls fishing gear. They’ve been implicated as a factor in the decline of alewife in Lakes Ontario, Erie, Huron, and Michigan. They are also a food source for fish including yellow perch, white perch, walleye, bass, alewife, chub, chinook salmon, emerald shiner, rainbow smelt, lake herring, lake whitefish and deepwater sculpin. Will they remain invasive if they play an important role in the food web? When will they no longer be considered invasive?

Spiny Water Flea in Media

![]()

This invasive species is a voracious ‘Alien’ found in lakes

https://www.barrietoday.com/local-news/this-invasive-species-is-a-voracious-alien-found-in-lakes-1100559

To gain the attention of the public, scientists took to making militant videos and using rhetoric that creates fear toward the spiny water flea. Consider this video with a fake newspaper clipping titled, “Spiny Water Fleas plan further invasion of inland lakes!”. In this video, the spiny water flea general is portrayed as a fearful character dressed in military uniform. The scientists living in the world of the spiny water flea begin to obsess, as they further reject the notion that the species cannot be controlled. “We begin to obsess about our different natures and cultures with a fervent nationalism, stressing the need to close our borders to those "outsiders." (Subramanian 2016). An act of obsession was closing the lockes (similar to a dam) along the Fox River to keep invasive species from entering the Great Lakes. Scientists and policy makers attempt to control the flow of the Fox River to the inland lakes, the reverse direction as well. Borrowing from Mel Chen, who theorized the animacy of lead in culture, we’ve done the same to the spiny water flea. This notion of animacy, objects and things gain a sense of animacy as part of culture. The reiteration of alien, also contribute to this sense of animacy as something ‘other’ to fear. Spiny water flea has been animated (as the military general) to being more controlling than it is. The spiny water flea will remain in the Great Lakes and multi-species (human and non-human) entanglements are becoming-with its establishment.

“Just an average invasive zooplankton gal hanging out in the Great Lakes”

Right away, this tweet is self-deprecating as the account uses the phrase “just an average invasive zooplankton gal” to describe spiny water flea (SWF). Introducing zooplankton gal in this tweet as average is belittling or undervaluing the species. This is also an attempt to work a humorous tone into context, to seem human. This account is mostly likely a single white female (SWF). Two things that suggest female are the use of “gal” and the profile picture (depicts an “egg-carrying female” – the common term used in western science in spiny water flea research). The twitter account holder has chosen to portray this invasive species as a woman.

The use of “just an average invasive zooplankton gal” parallels how women portray themselves as modest, and more often self-deprecate or undervalue themselves. In this context, this twitter account was created by a woman who is reflecting herself through the account. “Women are encouraged to see themselves as passive objects, unable to stand up for themselves or to exercise control over their own lives.” (Williams, 2017) The association of “just an average invasive zooplankton gal” perpetuates an idea of victimhood. It promotes a false and degraded sense of the SWF’s own position in the ecosystem. Juxtaposed to this, the use of “invasive” imposes the notion of threat onto the body of the female zooplankton. SWF as average, or a threat. Which is it? This account shows the SWF as being both. The SWF is not an average zooplankton, so the use of average here is specifically to connect the zooplankton gal to being an average SWF, a woman that is seen as a threat to society.

“Travel in my heart”

The mobile traveler is another notion placed on the SWF by this account. The spiny water flea is not in fact a traveler, but a passenger. Since, the spiny water flea was brought over to the Great Lakes in the ballast water of large ships, the traveler is an inaccurate descriptor. Instead, this is used to describe this species as a wandering traveler. And this traveler is not welcome in certain places, like the Great Lakes where she is “hanging out”. Tying travel to the invasive zooplankton insinuates that mobility from outsiders is a threat.

“Daphnia in my mouth”

At least in American media and advertising, women’s bodies are reduced to a mere sum of the parts. For example, SKYY Vodka, an American Spirits brand; McDonalds, a fast-food chain; and Dasani, a bottled water company, all have marketing campaigns that appeal to male desires (Scott, 2015). They each have advertisements that sexualize a woman’s mouth.

The placement of “daphnia in my mouth” is suggestive of the female as a sexualized object and effectively reduces the SWF to a body part. The bio could have said “daphnia in my stomach”, which would be more accurate as the Daphnia spend little time in the mouth during feeding. Daphnia are shredded up and sent through the “mouth” which is more of just a digestive tube than anything else.

The mouth is important to the ecological story of the SWF. Zooplankton are an important food source for juvenile fish. Zooplankton feed on algae and smaller zooplankton species. For example, Daphnia, a smaller zooplankton species, is generally part of the spiny water flea’s diet, but are also eaten by juvenile fish. The mouth size of fish limits what they can and cannot eat. Larger fish can eat spiny water fleas, while smaller fish can eat Daphnia. Vice versa, the mouth size of the SWF determines what zooplankton they can and cannot eat. There is no perfect way to trace the food web of juvenile fish, zooplankton, and algae.

“Ponto Caspian will always be my home”

This phrase explains where SWF comes from and that it will always be home, even if its present home is the Great Lakes. “Always be home” also points to the idea that no matter how much time passes, SWF will never be welcome to the Great Lakes. It will always be considered an outside threat, even if it has established an important role in the ecosystem. For example, the SWF is a food source for yellow perch. SWF competes with another large zooplankton for Daphnia, Leptodora kindtii, which is established all over the world, including Europe, Asia, and the Great Lakes. Why does Leptodora get native status to the Great Lakes, but SWF will not? Is it simply because before western science started to identify invasive species, Leptodora had already established itself in the Great Lakes? This phrase pieces together that the invasive zooplankton is from Eurasia, and makes them an outsider and female threat.

Which SWF are we talking about here?

SWF has been portrayed as female, proven by the “just an average invasive zooplankton gal” phrase. Piecing together that SWF is female, mobile, erotic, and an outsider originating from Europe, I suggest that @SpinyWaterFlea is depicting themselves as the Single White Female to appeal to male desires while simultaneously provoking fear by making the SWF a threat. Because the targeted group are mostly recreational fisherman and boaters, consisting mostly of white middle-aged men, this is a tactic that captures the attention of people that are likely to know about the spiny water flea, while also being the ones that are most likely to help in introducing them to inland freshwater lakes.

When Trump was elected in 2016, he promised to build a wall at the United States – Mexico border. He had also expressed support to limit legal immigration. By 2021, Trump will have cut legal immigration in half (CITE). Also, there was the ban on travel from certain Muslim-majority countries to the United States, later saying it was a geographical ban, not religious. As part of the domestic conversation around mobility, Trump is just one example of how mobility of certain groups is placed into the larger cultural conversation. Trump is also a prime example of accusing women as a threat, in order to protect himself from losing power. Trump administration adopted two new rules that gave entities objecting to contraceptives for religious or moral reasons – including for-profit business, insurers, and individuals – the option of giving no notice (of refusal to cover contraceptives) to the government or their insurers (CITE). This act of control over women’s lives at no warning from employers is a gendered issue in the U.S. No such issue exists to this effect for men. SWF is only a passenger as part of the invasive species discourse. It’s not SWF that is the problem, but the humans that carry them to new ecosystems that have been altered by humans. Removing gender notions from SWF in social media will also reveal the overlooked truths about spiny water fleas. One, they are food for yellow perch. Two, they have checks and balances in the zooplankton community and within their own species. By this, I mean when there is not enough food they stop reproducing asexually, and begin to sexually reproduce which allows them to make eggs that hatch when conditions are right. Invasive species research is important to understand the population dynamics of an ecosystem. Rather than a reductionist approach that focuses on the “harm” (referred to as “change” in scientific research) by one species, scientists and journalists should take a whole systems approach to discuss invasive species. Otherwise, solutions may be misguided.

Human introduction causes more harm tomorrow than today as globalization is ever expanding and causes harm to economic, environmental, and human health. Has globalization reached a capacity limit? Or will humans continue to find a way to affect every possible niche across the biosphere from micro to macro scale? This analysis makes a connection between humans and a micro niche, the zooplankton community of the Great Lakes, and draws a parallel to U.S. conversations around gender and mobility.

Lastly, in order to avoid perpetuating the notions of women and mobility as a threat while discussing the spiny water flea, the species should be referred to as what it is in itself. It can be called Bythotrephes longimanus, the widely accepted neutral and scientific terminology. Discourse around Bythotrephes should focus less on the species itself as the threat and more on human impacts to the environment that make Bythotrephes a mobile passenger (i.e. recreational fishing and boating). Find a clear pathway to the root of the invasive species socio-politico-ecological crisis, and not subjecting fear, women, and mobility into the discourse for our own entertainment.

- Edmund Burke, On the Sublime -

To control people and take away the power of the individual to act and reason, you create fear. As with the aforementioned AIS, culture has created fear around AIS. During my research on the spiny water flea, I felt myself fighting what can’t be won, a battle of the imagination. News articles and research paper titles shared the common phrases, dangerous invaders, silent invaders, or LITTLE THINGS BIG PROBLEM. People are fearful of spiny water fleas, and if they haven’t heard of them, then they are afraid of the sea lampreys, the zebra mussels, the round goby, or the Asian carp. Imagine a creature that has no mal intent. Rather, it’s just trying to live, the same as I do. I was afraid and willing to fight. But, turns out I was fighting myself.

Fear is driving people away from the heart of what drives biological invasions. The focus needs to lean more towards restoration, preventing habitat degradation, and protecting what habitat is left so the Great Lakes ecosystem can find balance. Humans are imperfect. There have been mistakes made, catastrophic mistakes – world shattering mistakes. So, why not admit that humans are the cause of these mistakes, shift the blame to ourselves that are responsible for introducing AIS into the Great Lakes? If humans are part of the system, then was it natural for the introduction of AIS in the Great Lakes? Was it inevitable? Darwin reasoned that these victories were inevitable. Different species might adapt to a particular ecological niche in different parts of the world. Put them in the same place, in the same niche, and one might well outcompete the other because it has evolved superior attributes.

I reflect on the research. Have I unmade what I learned about AIS? There is still a part of me that gets fired up about the spiny water flea spreading to inland lakes. But, for the most part, I think I have broadened my vision to explore the interconnectedness between nature and culture that includes spiny water fleas, the Great Lakes, politics, media, art, money, and researchers, like myself. Rather than obsess over the innocent creature, I rethink my own position in this natureculture story. I have noticed that I prefer not to call the creatures invasive species, but transported species. Tying the action of human transport to the name itself, gives context to the issue at heart – the real invasive species being humans. In my personal reflection, I feel that there is no fighting transported species, but becoming-with. Humans have to learn to live with the consequences of our actions, including transported species. This marks the end of the Great Lakes and AIS for me. I am dealing with transported species. The Great Lakes are not ending, but the way I have known them for the last 25 years has ended. I now see them as an ethos, with a lifeworld of its own. The next questions I have left on the table are pointed at corporations from the 1960s to present that pay researchers to study AIS. Are they part of a ploy to further this notion of fear around AIS in the Great Lakes? Are corporations playing the “scientist” to place blame for poor water quality and pollution on innocent creatures?

Bibliography

Balch, R. F., K. M. Mackenthun, W. M. Van Horn, and R. F. Wisniewski. 1956. Biological

studies of the Fox River and Green Bay. Bull. WP, 102.

Ball, J. R., V. A. Harris, and D. Patterson. 1985. Lower Fox River–De Pere to Green Bay Water Quality Standards Review. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

Burke, Edmund. 1767. A philosophical enquiry into the origin of our ideas of the sublime and beautiful. London: Printed for J. Dodsley. 34-133.

Cattelino, Jessica. 2017. “Loving the native: invasive species and the cultural politics of flourishing” in The Routledge Companion to the Environmental Humanities. 1st ed, Routledge. 129-137.

Egan, Dan. 2017. The Death and Life of the Great Lakes. New York: Newton & Company. 7-49.

Gagliano, Monica, John C. Ryan, and Patrícia Vieira, eds. 2017. The Language of Plants: Science, Philosophy, Literature. Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt1nxqpqk.

Goodeve, Thyrza Nichols. 1999. How like a Leaf: An Interview with Donna Haraway. New York: Routledge.

Haeckel, Ernst. Generelle morphologie der organismen [General Morphology of the Organisms]. Berlin: G. Reimer, 1866.

Haraway, Donna J. 2016. Staying with the Trouble. Durham: Duke University Press. 1-29.

Robert Costanza, Richard B. Howarth, Ida Kubiszewski, Shuang Liu, Chunbo Ma, et al… 2016. Influential publications in ecological economics revisited. Ecological Economics, Elsevier, 123, pp.68-76. ff10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.01.007ff. ffhal-01286862f

Seidler, Reinmar, Kamaljit S. Bawa. 2016. Chapter 22 in Keywords for Environmental Studies, J. Adamson, W. A. Gleason & D. N. Pellow (eds.), New York and London: New York University Press. 242.

Subramaniam, Banu. 2014. “Signing the Morning Glory Blues” in Ghost Stories for Darwin: The Science of Variation and the Politics of Diversity. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. 70-91.

Subramaniam, Banu. 2001. "The Aliens Have Landed! Reflections on the Rhetoric of Biological Invasions." Meridians 2, no. 1: 26-40. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40338794.

US Geological Survey. 2020. Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database. Gainesville, Florida.Accessed December 2020.

Vasilogambros, Matt. 2014. “Minnesota Politician Thinks Asian Carp Name is Offensive to Asians.” The Atlantic. March 31. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2014/03/minnesota-politician-thinks-asian-carp-name-is-offensive-to-asians/437484/ (Accessed December 15, 2020)

Von Uexküll, Jakob. 1934. A Stroll through the Worlds of Animals and Men. International Universities Press, 1957. 1-80.

Walsh, J.R., Carpenter, S.R. and Vander Zanden, M.J. 2016. Invasive species triggers a massive loss of ecosystem services through a trophic cascade. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113: 4081-4085.

Zimmer, Carl. 2014. “Turning to Darwin to Solve the Mystery of Invasive Species.” New York Times. October 9. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/09/science/turning-to-darwin-to-solve-the-mystery-of-invasive-species.html?searchResultPosition=2 (Accessed December 14, 2020).

“The Visual Effects Behind Stranger Things’ Monster.” Form Labs. October 30, 2017. https://formlabs.com/blog/visual-effects-stranger-things-monster-demogorgon/ (Accessed December 15, 2020)

University of Wisconsin Extension. 2016. “Stop the Spiny Water Flea Invasion.” Youtube video, 7:10, May 31, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=krzs5ukbRQE (Accessed December 15, 2020)

Conflicts, confrontations, and resolutions are normal… a part of life. As much a part of life as it is to breathe. Breathe in, I share an opinion on one hand, breathe out, I share a conflicting opinion… in the same breath. In between the in and out is where I really start to liquify what I thought at one time is not so simple, and that I must consider taking another breath.

Which do you prefer, the lake or the ocean? Depends on the place. Maybe, it depends on the how much that place feels most like a home.

My home was in a northwest suburb of Chicago, called Barrington. Today, when the word Barrington comes out of my mouth, I immediately feel a repulsion. Its mouth feel brings visions of teens in their hummer vehicles pulled by white, shining horses off to the prom. Moving to Rhode Island, I started to visit and then work in Barrington, RI which was more or less the same but this time Teslas and Jeeps packed into parking spaces like glimmering jules organized behind the gas station counter. Both offer a tempting illusion.

Where I grew up, there was a shallow pond with splatterings of duckweed in the summer, and frozen ice bubbles dotting the surface like a million moons in the winter. We called it Tower Lakes and kids ran around barefoot through private yards to the beach, never missing a day of sunshine.

Invasive species were not on the mind of 10 year old me. Not until, when climbing around the shoreline over submerged rocks I got a razor slice in the bottom of your foot from a little bivalve called the zebra mussel. Then, for a brief moment, they are a nuisance but I wouldn’t go as far to say they had to be removed. As a child, you learn these lessons. And, one of them from that experience was that water shoes are never a bad idea along a rocky shore.

From Tower Lakes, I was fortunate that Lake Michigan was only a short train ride away. I didn’t stray too far from home and moved to the city after college to work at Lincoln Park Zoo. Every morning at 7am, I’d grab a granola bar and hustle my way along Chicago’s lakefront, fighting the strong winds that ripped past my face.Winter forced me into a 50-passenger packed bus avoiding that cold lake wind which would shock your bones and numb your hearing. The sight of Lake Michigan as I stepped off the bus and turned to cross the street was enough to energize me for the day. Even if it did bring tears to my eyes. Not from the icy winds, but from joy, anger, and sadness. Lake Michigan could make me smile, cry, scream and laugh in the same breath..Was it that I was in bewilderment and my brain just couldn't pick one emotion to settle on?

Do I prefer the lake or the ocean? I can’t decide because they both carry a deep, lonely, and mysterious past, present and future. To understand me and why I have this attachment to the Great Lakes, a good example would be to examine my closet. On a hanger in the back, you will find myGreat Lakes sweatshirt that is covered in shipwrecks along with their date, coordinates (or none if they never recovered the ship), and the number of people perished. It’s a lake with magnificent stories and only she knows how they end. That’s deep.

On the note of loneliness, I can relate to Lake Michigan. When I feel a sense of loneliness and emptiness, it settles when I stare out at the horizon of the lake thinking of the number of people who have been along this shore and uttered the same thought for generations.

Tied up with all these feelings are the mysteries of the Great Lakes. They’re not called Great for no reason. Tens of millions of Americans rely on the fresh water for drinking, sustenance, work, and recreation. Out of the world’s supply of surface fresh water, the Great Lakes hold 20 percent. The great mystery is why are they dying? Why does a part of the country with so many resources, and with so much to lose, not reach a resolution and imagine what a deeper, reciprocal relationship with the Great Lakes would look like?

Facing the Great Lakes

When I ask myself, do I prefer the lake or the ocean? To me, I can’t decide because they both carry a deep, lonely, and mysterious past, present and future. No one understands me and my Great Lakes sweatshirt that is covered in shipwrecks with their date, coordinates (or none where they never recovered the ship), and the number of people dead. People ask me why do I like the Great Lakes so much? Because, I related to them. I, too, feel a sense of loneliness and emptiness at times. It will become clearer as to how the Great Lakes and I share these feelings. I believe it has something to do with semiosis, a system of meaningful signs. Language is more than the audible communication carried out by humans; it encompasses the complexities of intersubjective and interspecies dialogue, involving nature and humanity (Gagliano 2017). The Great Lakes, as an entity, has a system of meaningful signs that over time, humans have learned and passed down through generations. Those signs mirror a reaction in myself. This is the Great Lakes call for help, to be set free of its suffering.

Tens of millions of Americans rely on the fresh water for drinking, sustenance, work, and recreation. Out of the world’s supply of surface fresh water, the Great Lakes hold 20 percent. The Great Lakes and humans share an extricable relationship, at least, through a dependence on drinking water for 30 million people. A Greatrelationship with the Great Lakes, should be a two-way street. But, from the perspective of the Great Lakes, I’m sure the last two centuries has felt more like a one-way street. Geologically speaking, the Great Lakes has not even batted an eye at this blip of suffering.

Who am I to the Great Lakes?

Living in naturecultures means developing a self-reflexivity, continually wrestling with the interconnections of natures and culture, politics and science, the humanities and the sciences, and feminisms and science (Subramaniam 2001). I self-reflect on research I conducted my senior year on an aquatic invasive species (AIS) in the Great Lakes. To supplement my reflection and lessons, I will examine other cases of AIS as well, including zebra mussels, the round goby, the Great Lakes sea lamprey, and Asian carp. I will attempt an imaginative reconstruction of the spiny water flea and outcomes of my research. I, as the human actor performed scientific work in relation to many objects and subjects of study. Following Banu Subramanian’s inspiration from Italo Calvino, I will approach this essay as a mental exercise of undoing my disciplining. This is important because my practice was learned under a patriarchal and strict rule of western scientific epistemology. My focus was on the AIS, but I want to reject that narrow vision to expand outward peering into the ethos, the lifeworld, the umwelt (Von Uexküll 1934) of the Great Lakes. This will help relate my studies to people, multi-species, politics, art, global trade, money, and all things that become-with the Great Lakes.

I will situate myself back onto the boat in Green Bay, Lake Michigan and recreate a map of my knowledges and methodologies. I recognize that I learned a particular and refined method of classifying, analyzing, and scientific writing. This will challenge me as I will have to turn the gears back and begin writing a new narrative challenging my own studies and the approach to raising public awareness of AIS, as well as posing the question that no aquatic ecologist, or policy maker, studying the Great Lakes wants to answer… is it time to give up on preventing the spread of AIS? Who is really behind the degradation of the Great Lakes? Who or whom is the invasive species?

How I landed in the Great Lakes

In 2016 and 2017, a pattern of unexpected events led me to captain my own small ship… as I called it. In reality, it was a small university-owned skipper boat I pretended that I could take off in that boat anytime. I’d leave all my studies behind and let Lake Michigan be my teacher. I was a student researcher in an aquatic ecology lab studying the impacts of AIS on the Fox River and Green Bay ecosystem which is part of the long-outstretched arm of water separated by the Door County peninsula in Lake Michigan. It is also known as Death’s Door due to the unpredictable currents, capsizing small skippers.

The summer of 2016 was a scorcher. I was 20 years old living in a small dorm on campus with no air conditioning and a cup of noodles, a bag of potatoes, and carrots dipped in peanut butterFor one week, we lost power to the dorms and I slept in the lab. The lab was my escape from outside where the sidewalks could cook a full egg and sausage breakfast. My time was split either in the lab or on the windy shores of Green Bay with our research boat, The Daphnia.

My lab mates were exceptional and are some of my best friends to this day. Four women striking down any misogynistic comments on our abilities, like backing up the boat or wondering what women were doing headed out to choppy waters by ourselves lugging heavy research supplies back and forth from the van.

Long days were spent collecting samples of fish, invertebrates, zooplankton, algae and measuring biodiversity. The Fox River is an important route that allows for cargo ships to dock in Green Bay, WI. As we were going out to collect samples, one large cargo ship passed us. I could feel the vibrations of this obscene object move through our small boat out through my fingertips. I was unsettled, watching the large ship go through the shallow canal.

Because my true loves during college were The Daphnia and Lake Michigan, I developed a research study on a subject that would require me to take her out on the water for another summer. My subject was a type of aquatic invasive species (AIS) called the spiny water flea, a relatively large zooplankton that has a long spiny tail. At the time, my professor was asked to monitor their population in Green Bay and to note any interesting findings. I’d head out into the choppy waters of Green Bay and toss our zooplankton net out behind the boat to tow along collecting little water fleas. I began to notice that the color, texture, and viscosity of the water would change from day to day. How were water quality and zooplankton ecology connected? How had the introduction of the spiny water flea in Green Bay affected the viscosity of algae in the water? What tiny organisms were intertwining to create that gelatinous, stringy green saliva in the water?

These questions guided me to understand how the spiny water flea shifted competition between predator and prey relationships that resulted in visible and cultural changes to the ecosystem. Though it would seem these changes happen under the surface, there is an entanglement of species, fisherman, chemicals, water quality, politics, morph our conceptions of political, economic and cultural contexts. However, this naive version of myself was certain that the spiny water flea was the main actor responsible for the negative impacts on Green Bay’s ecosystem.

Certainty encourages looking from far away. Certainty leads to a closed door. I needed uncertainty to float between the breathing in and the breathing out. What I lacked in my certainty was the history of Green Bay. More context to describe what happened leading up to the establishment of the spiny water flea in Green Bay would help understand why they were there in the first place. There were more factors at play in this natureculture story that I had yet to uncover.

Speaking of Natureculture

Nature and culture, are co-constituted, entangled processes of semiotic as well as material. An analysis of my past research and multiple AIS stories, emerges a history of “naturecultures”, tracing and elaborating the inextricable interconnections between natures and cultures (Subramaniam 2001). What I am trying to understand about AIS is hidden underwater, above ground, and within the subterranean of the Great Lakes. Habitat, biodiversity, history, geology, science, politics all becoming-with this “natureculture” story.

Through this essay, I will tell stories of AIS that are important to understand in the inextricable connection between nature and culture of the Great Lakes. My goal is not to ignore the spread of AIS, but to reimagine their significance and deconstruct the fear around AIS. To what extent is aquatic invasive species (AIS) management necessary? How has the spiny water flea (discourse) shaped politics and culture of the Great Lakes?

Socio-ecological Thinking

First, I should take a deep breath and remind myself of the definitions pertinent to this story. The term ecology has gone through many definitions since the 1800s. “Ecology” was coined by the German zoologist Erns Heakel in 1866. It was generally defined as organized knowledge about a vast array of relationships among species and their environments. Reading from Keywords for Environmental Studies, I understand ecology as the observation of interrelationships with and within organisms, ecosystems, and human culture which not only shape the natural world but also shape situated knowledges of our present and future of humanity. Ecology as I approach my thinking, involves the environmental and social sciences working together (Seidler, 2016).

A Brief History of The Great Lakes

Geology

For a long period of time, humans have caused habitat destruction on the Great Lakes. Impacts have risen due to industrialization and globalization, and are a result of physical, chemical, and biological changes to the environment leading to species extinction, habitat pollution, habitat loss, and non-indigenous species introductions. Before humans, the origin of the watershed is a product of multiple glaciations during the late Cenozoic as well as redirected drainage, particularly during retreat of the last ice sheet.

As fate would have it, in the geological becoming of the land separated the water into the five Great Lakes, Erie, Huron, Michigan, Ontario, and Superior. At one point, the water flowed through them as one on the surface, but scouring of the rock created deep depressions for the five Great Lakes to become what they are today. Though they are called the Five Great Lakes, the water is always flowing between them down a slow-moving river west to east.

The Niagara Falls cascade from Lake Erie into the waters of Lake Ontario below. It is estimated that in 50,000 years the falls will disappear and with it the cliffs that have separated the upper Great Lakes from the Eastern Seaboard. The slow-moving river will become fast, creating a new geological landscape through forceful erosion. Eventually, the once Great Lakes will lower until it meets sea level Though that future is far away, it does beg me to imagine how that change begins to shift the midwestern landscape. All those dairy farms, corn and soybean fields, would surely drown in wetness, as these floodplains continue to expand.

People

The land was covered in dense impenetrable forest and was navigable only by canoe. Residing in the region for many generations prior to settlers, were the Miami (also called Maumee). The language spoken in the Great Lakes region was Algonquin, and other First Nations resided in the region, including Ojibwa, Ottawa, Menominee, and Potawatomi). French traders and explorers were the first Europeans to arrive in the Great Lakes region between 1550-1600. The king of France sent them to chart the river systems as highways facilitating access into the interior of North America. The Great Lakes include, Lake Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie, and Ontario. They hold over 5,400 cubic miles of water – therefore accounts for 21% of the world’s surface freshwater. These inland freshwater seas, provide water for drinking, shipping, power (electrically and conceptually), recreation, aquatic life, agriculture, and more. North America relies on the Great Lakes for 84% of their surface fresh water.

Ecological Economics

The Great Lakes are an ecological economy, with natural capital in water supply, climate regulation, habitat for species, food, recreation, transportation, and cultural amenities. Economy is not independent from ecology, or the natural world. Rather, it is an ongoing effort that integrates the study of what is desirable to what is sustainable on our finite planet (Costanza 2016). That is why I describe here the transdisciplinary field that integrates humans and the rest of nature as ecological economics (Costanza 1991; Costanza et al. 1997; Daly and Farley 2004; Costanza 2016). Integrated with social and cultural capital, the Great Lakes provide a hub where natureculture connections forge through social networks, cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, trust, and sense of belonging.

Becoming-with Global Trade

There are five ports in the United States, including Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Duluth, and Milwaukee. Canada’s major ports: Toledo, Port Colborne, and Toronto. Coined an Economic Powerhouse, coastal areas represent strong economic and ecological engines in the Great Lakes. For every dollar spent in Great Lakes Restoration Initiative funding, an estimated $3.35 in economic activity is produced. A total of $3.1 trillion gross domestic product, employs 25.8 million people, supports $1.3 trillion in wages and contributes to this developed economy. This shipping system is called the Great Lakes/St. Lawrence Seaway . The story of the Seaway is quite dramatic. It was one of those ideas where you look back and wonder how nobody foresaw this becoming a nightmare? But, during the 1950s when the Seaway was constructed, the race for control over industry and shipping was well underway. Global, national, as well as regional competition drove the opening of the Seaway. At one point, the Seaway’s oversea shipping peaked at 23.1 million tons per year in 1970. Why the Seaway was constructed is complicated. One major reason was to increase exports to foreign countries. It was the gateway to the rest of the world and every Great Lakes coastal city wanted a piece. It was about expanding power, capital, and control. At the time, Chicagoans had a “second-city complex” that they wanted to subside. Having access to a port out to sea would allow them to compete for the “first-city” beating NYC. As I’ve learned, humans are prone to mistakes. After great costs were expended to build the Seaway, which included flooding large towns and people being forced to move within a one-year notice, it barely makes a dent to match the shipping pace of trains and trucks. Now, less than 5% of the Great Lakes shipping industry is overseas. Duluth paid millions for the construction of a special shipping crane in hopes of enticing shipping container imports. It has remained idle for 20 years! A large part of this shortfall was that the Seaway is covered in ice over the winter and has a shorter shipping season compared to ground shipping. The Great Lakes coastal cities wanted to increase their capital through exports. In their struggle for power, they also invited aquatic invasive species into their ports. But I’m careful not to point the finger at foreign imports to be at fault for this. When I trace to the origins of this project, it was the United States and Canada that funded the Seaway.

Aquatic Invasive Species and the Great Lakes

Since the Seaway was opened in 1959, it has acted as a corridor for aquatic species to traverse. This e journey isn’t on their own. They are trapped in up to six million gallons of ballast water, which is used to maintain balance of a ship. Once the ballast water is discharged from a ship, any organisms that were picked up at its place of origin are released in exchange for cargo. Within these billions of organisms could be a traveler that is forced to make its home in the freshwater of the Great Lakes. They need to survive in their new home and if they can, they will.

Aquatic Invasive Species (AIS) or Non-Indigenous Species (NIS)

Before discussing several cases of AIS in the Great Lakes, we should pause to define this area of science that I spend most of my time thinking about, called invasion biology. From an aquatic ecologists’ perspective, I prefer to not isolate invasion biology because it is not a separate study but an integrated part of ecology. Rather, I prefer to think about my studies from the standpoint of community ecology. As an aquatic ecologist, I investigate the factors that influence community structure, biodiversity, and the distribution and abundance of species. These human and non-human factors include interactions with the abiotic world and the diverse array of interactions that occur between non-human and human species. Invasion biology is the study of invasive organisms and the processes of species invasion. The USGS describes that biological invasions are the second leading cause of extinction behind habitat destruction. Habitat destruction weakens the integrity of an ecosystem and makes it susceptible to invasive species. Without habitat destruction there would be no open door for species invasion. If humans are the cause of habitat destruction, then the species invasion that seems of significance would be the invasion of humans and its impacts on the planet. My point being, biological invasions cannot be the second leading cause of extinction. Habitat destruction is the umbrella for all other causes of extinction. The point of hierarchy is mute.

The Lake Sturgeon

One of the planet's greatest wonders, there is nothing else like the Great Lakes on earth. Theese lakes sustain a variety of aquatic species, including the endemic Lake Sturgeon. These prehistoric, dinosaur fish, can travel up to 1000 miles. On one of my trips to the Shedd Aquarium in Chicago, I entered the Great Lakes exhibit. They have a touch tank where several of these large sturgeons live. They swim about with their long bodies bumping against the tank. Each time they hit the side of the tank; their massive weight sends reverberations through the floor up into my body. Their skin is shiny, black as the night, and smooth to the touch. When I pressed two fingers against their skin, it felt unlike any other fish. They don’t have scales the way most freshwater fish do. Instead their skin is partly cartilaginous skeleton, so it feels like a slimy balloon stretched thin over pebbly rocks. Lake Sturgeon are now extinct in most of its ancient spawning grounds due to overfishing and pollution. The industrial revolution lead to an appearance of mercury and lead in the Great Lakes. Also, the flushing of raw sewage, dioxins, acid rain, PCBs, and fertilizers into the lakes decreased their population by 99%. By the 1980s things started to improve due to governmental regulations on air and water pollution.

The Bald Eagle and Sea Lamprey