Writings from the playa

Writings from the playa in the high desert of Oregon, US

By Casey Merkle

Winter 2023

Where am I?

Locating… locating… I pull out my digital device to open a map. The one that reduces my body to a glowing, blue dot. Where is my body? Where is my blue dot?

I have located myself in the western half of the US. This is my first time northwest and I am humbled, loving and in love, bewildered, curious, and small - literally I have shrunk here. The surroundings are overwhelming and magnificent, growing higher and higher as I traveled east to west.

There is a mountain range dotted with trees located behind me where I will be staying for the next month. Truly, these trees are twice the size as the ones back home in the midwest. They climb thousands of feet up the mountain through the snow. Some are giant toothpicks, left from a wildfire a few years ago. For my own comparison, I pause and picture the hill I grew up on - it is a tiny tic tac in my mind. Water collects in small lakes at the base of the mountains. Like a mirror, the water offers a still reflection of the mountains towering above. It is curious how this treacherous desert can settle into such a stillness.

“The desert doesn’t give a fig about ranch names, place names, me, whether or not I spent time on the South Fork of the Crooked River.” - Ellen Waterston

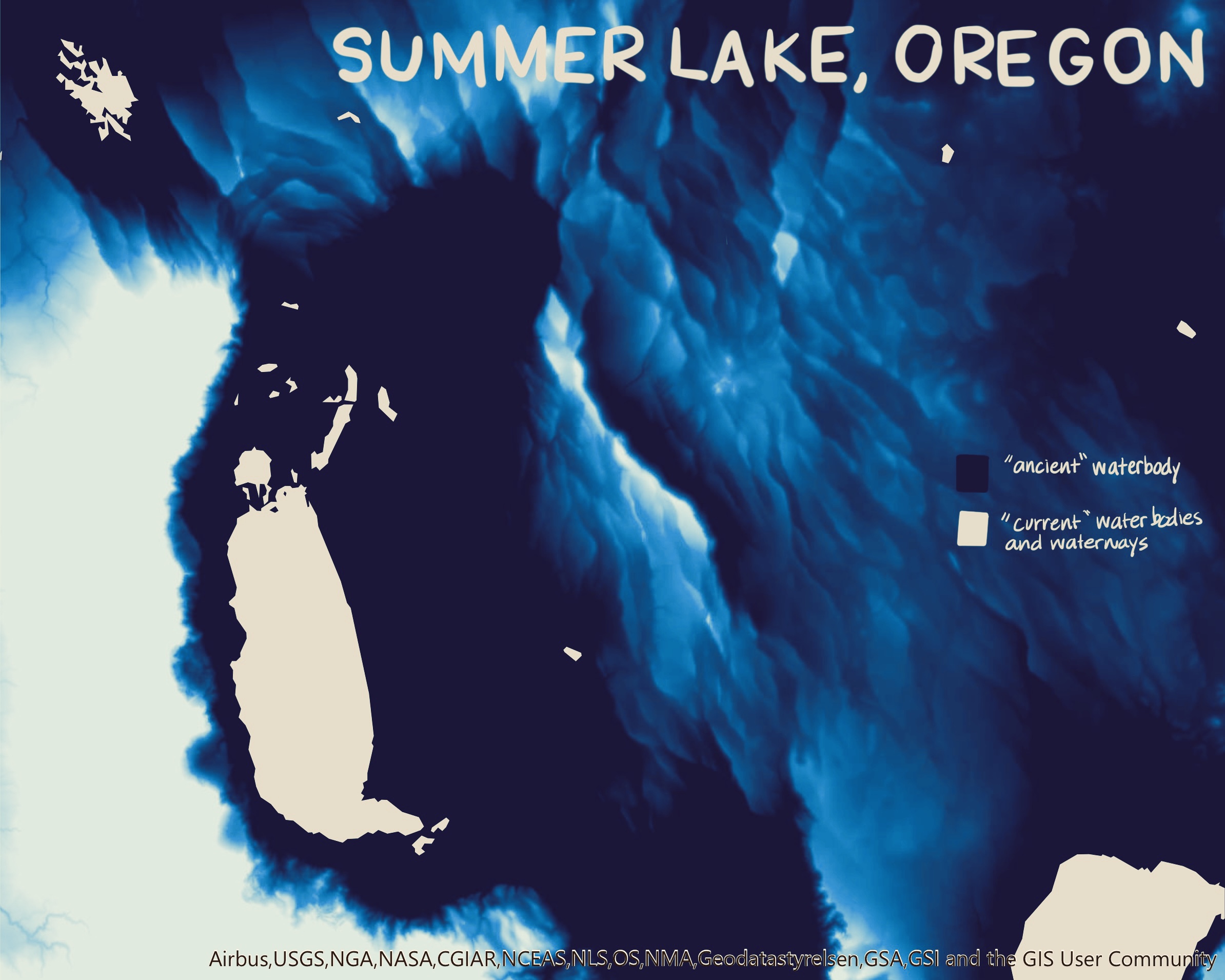

The blue dot shows me I am in the high desert of Oregon. Today, it is a town called Summer Lake, OR. The land and water that surrounds me makeup the ancestral homelands of the Paiute and Klamath Tribes. In 1850, the Paiute were forcibly removed from the lands in the high desert. Their presence remains here on rocks, high in the mountains, across Summer Lake, and in the roots that hold the soil. Roots that are still today gathered by the people of the Warm Springs, Wasco and Paiute Tribes, known today as the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs. And, the Klamath Tribes - the Klamath, the Modoc and the Yahooskin-Paiute people, known as the mukluks and numu (the people), who have lived in the Klamath Basin of Oregon, from time beyond memory. I make this acknowledgement, because stories about relationships with the land can not be gathered or retold without recognizing the roles that Indigenous People have played in shaping these lands today and since time immemorial.

It is with honesty, I share my concerns before settling in. One, the nearest grocery store is an hour drive. Unless, you would like to take your chances on expired milk or the enticing canned, smoked oysters. Two, no cell reception. And three, I make a pretty easy snack for the cougars. Later on I learned that cougars are quite cautious animals and it would be extremely rare to come across one. The closest I got was to a bit of scat.

I threw all of my concerns out the barn door. Fears start to sound silly after you listen to them for a while. It’s okay to listen, but I’ve learned to not let them control my life. And, I’m so glad I acknowledged the fear of moving out of my apartment and running out of money. I realized that like many people, I was just afraid of change. Oh, how this place has changed my heart!

On the playa

My cabin is situated along the western edge of a body of water called Summer Lake, known as a playa. Playa is a dry and flat area, occurring at the lowest point of an undrained desert basin. Shallow, alkaline lakes appear during the wet period and disappear during the dry period. Appearing, then disappearing, and so on.

Summer Lake is a point of ephemerality. It waits to be refilled by the spring beneath Ana Reservoir. The water travels over a few miles from the north to south through Ana River, catching along its path some mountain streams of snowmelt. Generally, at highwater it is 15 miles long and 5 miles across.

I learned all of this from time spent looking over maps, hiking, driving up service roads, walking along the water, reading, talking to some folks and some plain old meandering. It started with the map of the watershed. From there, I located the mainstream, Silver Creek and its waters, including Ana Reservoir and Ana River, which end in Summer Lake. To me, this is different from my home on the east coast. There, most water goes into the ocean. But, here the water transforms through evaporation or sinks deeper into the subterranean.

In the future, some people worry that the spring, snowmelt, and rain might not be enough to bring Summer Lake back. I pause on that thought and watch as water droplets are carried over the playa by a single, tiny cloud. It is traveling fast across the shallow lake. I watch it disappear, floating beyond over the mountains, wondering what it would be like to ride on top of that cloud. I want it to take me to a world that is ephemeral. A world that appears when it is in balance, and disappears when it has passed its limits.

This “rugged” landscape is soft, layered, and compassionate. Yes, at times there is emotional chaos rumbling through on the back of fast and strong winds. But, because it is dry, the wind here feels like a warm embrace. It doesn’t slice my face quite like a Chicago lakefront wind. It rushes at me fast, but like a lovers kiss, it lingers leaving a static current that races all the way to my toes. I could easily lay under the tall, swaying grasses forever and watch the sunrise day after day. Until, even the coyote wouldn’t notice me.

There are five residents here with me at the playa. We cook dinner in the commons some nights, dreaming up adventures we will have over these next few weeks - one wants to make it across the playa without trapping herself knee deep in the mud. My journey will take me around the playa to explore the plants and waterways, collecting stories from the people living here.

My cabin is not too small and not too big - it’s my ephemeral world - where I can escape temporarily into a void of empty thoughts. There is a wrap around porch with two large sets of sliding glass doors that open out to the back porch. Their curtains pull back to reveal the full landscape of the playa. First, I see the rippling waters of the pond, then the tall grasess - bunchgrass, rabbitbrush, sagebrush, olive trees, pines, and more that I want to touch, understand and with which I'd reach a first-name basis. Following the brush, there is mud - gray and glossy mud, like quicksand, that stretches for miles.

The second day there, I decided I would walk through the mud just to the point where I could touch the water of Summer Lake. A few times I thought I was a goner - sinking deeper into the mud. The suction from the mud pulled me in so deep and the more I fought, the deeper the mud pulled me down. To escape, I had to catch the mud off guard. I’d let myself sink in, but then all at once with every ounce of strength I had in my core I’d lurch toward freedom.

Trekking around the edge of the water, I can see the marks of dried salt from where it was the day before. The lake is drying up. These lines are normal - an everyday fluctuation that creates an edge, a wide edge for all sorts of plants, insects and animals to thrive. But, the invisible lines, or the margins, of these habitats and ecologies have shifted greatly over time.

Fifty years ago, it was a much different story. And, looking to the north as Summer Lake’s sister, Silver Lake, I think about how much time Summer Lake has left before it is permanently gone. Today, Silver Lake is gone and the wet season hasn't come back for the last couple of years. Lake County, where Summer Lake is located, just recorded its fifth driest February in history and its second driest year to date over the past 128 years (U.S. Drought Monitor). Google maps won’t show this, but the farmers and wildlife rangers are well aware. Hunters, too, who will wonder where all the waterfowl have gone when this destination for migratory birds dries up.

The water bubbles up at Ana Reservoir, an underground spring, surrounded by a small neighborhood of cabins with retirees, ranchers, crafty individuals, and “bad businessmen”. Ana River bends her way from the reservoir, feeding canals and small lakes through the wildlife refuge that is a flyway for migratory birds, like the spoonbill and snow geese. They rely on the wetland that Ana River supports. Without the water these birds have to fly another hundreds of miles to find suitable habitat. This will be difficult, as wetlands are steadily decreasing in the US.

I recently read “Walking Wetlands”... a few times. Soaking in a new concept of wetland rotations sparked a lightbulb moment. Wetlands suffered the consequences of water management by the US Bureau’s infrastructure plans. Wetlands that have been drained or leveed, can not reclaim the habitat through natural forces over time. This is due to the lines that have been constructed to separate land and water. Removing the lines may replenish walking wetlands, moving wetlands across the land. On the other hand, moving water in this way would tinker with the availability of water for agriculture. What’s to be done to balance the availability of water for wildlife and for farmers?

Water is the arteries of the earth. When an artery is blocked off, the land changes and dries up. That piece of land that depended on water for it’s soils, plants, animals may drastically change to the point of no return. To return the water back to wet(dry)land it requires management. I see more clearly the unforgiving, albeit delicate, nature of water management. I can’t help but wonder what would happen if the Hoover Dam broke? Where would the water go if freed from the line?

As I stood at the edge of the reservoir with these thoughts, I looked up at the 10 feet of exposed soil, roots, ancient seashells and fish skeletons from what was once a large inland sea. “Environmental change is constant, although it is not always perceptible or predictable.” From where I was standing, how could you not perceive this drastic environmental change? Summer Lake was evaporating right before my eyes.

On Bunchgrasses and bending with the wind

![]()

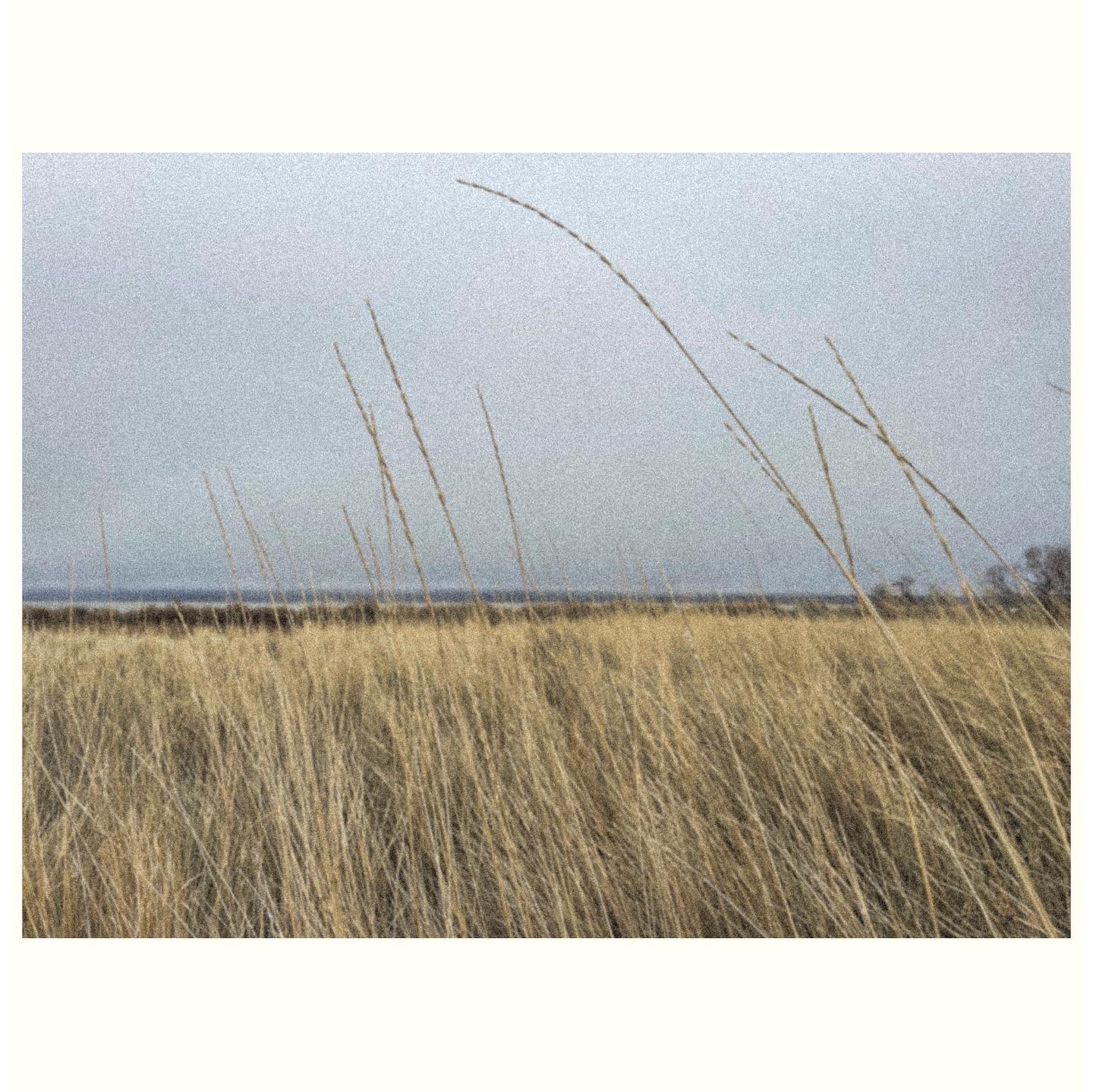

I walk while the sun sets behind the rim. I walk towards the playa, each step less hesitant than the last. I hear the mud crack and crunch beneath my feet, still frozen from the cold night. As I take a large step down into the sea of sagebrush I hear a thump. Was it a coyote I startled?

![]()

My fingertips graze the tall grasses. They have a weight to them. As I brush past with my hand, I can feel them pushing back. There is a strength in these grasses that keeps them upright. Standing tall through 80 mph katabatic winds, drought, herds of mule deer, and the rare outsider, like myself who has come to understand them. I want to partner with these grasses. Have them tell me their story and why they stay. How many lives have they watched begin and end here in the playa?

![]()

The plant I am particularly drawn to is the bunchgrass, Idaho fescue. It has a heavy top when dried, conspicuous and sturdy. When I hold the seeds in my hands they are smooth, sand-colored; some are bleached white from the sun. The long stem is hollow, but forgiving. It bends with the wind, allowing the katabatic to march a strong whiplash right on through.

![]()

And, this katabatic wind. It is not your average wind. It’s pulled through the playa. Creeping up the otherside of the rim, climbing higher and higher. When it reaches the top about to spill over, that's when you run and hide. The katabatic is flung into the desert heat below so fast it can reach speeds of 100 mph. How do these bunchgrasses stand the constant winds blowing them in a downward bend? I can barely stand a 5 minute walk through Chicago with the wind tunnels blowing my hair into a chaotic mess.

For a moment, I felt l was home in Illinois. The tall grasses remind me of a time somewhere deep that is not a part of my present life, but a part of the long ago lives that walked through prairies where buffalo grazed. The flatland here is familiar and comforting. But it’s surrounded with massive reminders of a deep geological past. Had it been yesterday that the Chewaucan River ran over this playa flooding it with 4,000 feet of salty water? When this thought takes over, I turn to the rim and ascend higher to overlook the flatlands of the playa. I close my eyes and imagine sea birds flying about, waves splashing against the face of this cliff, and feel the cool mist of salty air against my cheeks and lips bringing me a taste of my home on the east coast. I’ve made many places a home, but I am here right now looking out at the flatland and home feels far away.

In the suburbs of Chicago, my movements were interrupted by large strip malls, highschools, and highways. There were pockets of open space set aside, divided, and managed where suburbanites like myself could walk manicured paths. I was lucky to live in a neighborhood with many trees and a large pond for swimming and paddling. It was a quiet area, not much happened. Until the fish kills started and I became worried. Shortly after, the algae started to turn turquoise and goopy. It was a noticeable change from the filamentous, dark green plants that would stick in clumps to your paddle.

![]()

I have always been consumed by the questions around humans and nature. Why are they treated separately when they are so deeply woven together? In college, my classes enforced scientific classification, but also to think critically and to question everything. I moved to the city of Chicago after graduating with a degree in biology, and a strong love of lakes and ponds.

It wasn’t long for me, I realized I couldn't do city life. But, I wanted to keep my relationship together, so I followed a man to Boston. The relationship ended when the pandemic began. I felt shame for a long time, in letting go of something that we both spent years building. The time was right for us, and I moved to Rhode Island for more school.

There, I cultivated a deeper appreciation for slowness and solitude. I explored places along the coast, went inland to find waterfalls, and climbed down rocky inlets. Many threads began to fray - navigating relationships, school, family illness, covid, multiple jobs became all I was. After graduation, I taught kids bike safety and it was the second best summer of my life. I only left Providence for the waves, realizing that summers in Rhode Island are best spent avoiding the tourist-packed beaches, and finding secret spots inland, along rivers.

![]()

I looked outside myself and questioned all the things I thought I wanted, a steady job, a place of my own, a clean apartment, a new car, consumed by the life I've been told I should have. Had I grown used to the standard that work should be turned into income? My energy is income, transferable only by the slide, insert or tap of a credit card. That energy, my energy, is turned into tangible things like my apartment, the clothes on my body, the food in my fridge, the guitar that I dream of each night. The wheel kept spinning, even though it fell off the track. I was not grounded, I was spinning. I was structural, unable to bend like the bunchgrasses do. Just like that, I left. And, I started to bend with the winds that brought change. I was headed to Oregon.

![]()

I walk out on the playa to follow the path of bunchgrass. I can see cracks forming in the mud, where water is descending back deeper into the earth feeding the subterranean waterworld. It is a mysterious network of massive underground rivers and ephemeral streams. Do the bunchgrass know this? Is this part of their dependency? Where water runs beneath, is that the path they follow?

![]()

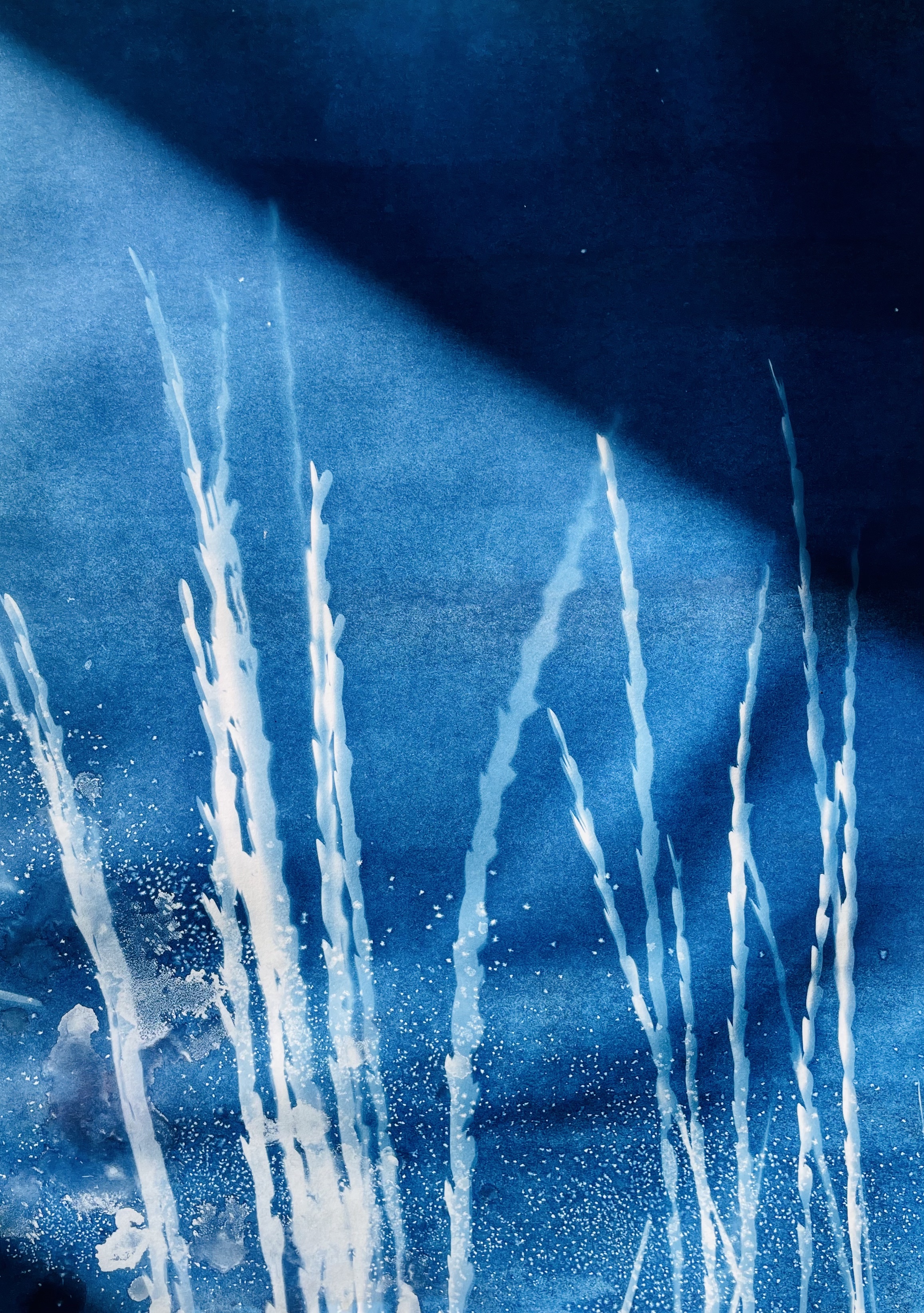

The Idaho fescue, this beautiful bunchgrass, has me in a state of captivation. I collect more and take it back to the studio. Somehow I want to embody the movement bunchgrass makes in the wind. How it gently bends all in sync with each other, leaning on its neighbors. I try a few techniques and play with cyanotype printing (see Ann, the Photograph, and Cyan). Tying them in bunches works surprisingly well - who would have guessed? The tops leave a beautiful wave-like pattern across the page and I am pleased. My mind does not want to stop there - what else can these bunchgrasses offer?

![]()

Can you make me some paper? Yes, they very much can and they show off their texture in the process. The paper left behind some of their fibers - unable to be sliced into tiny particles by the blender - and I am pleased. Not only by the paper, but by their strength. These fibers are built to withstand katabatic winds. By making paper, I feel I am capturing them in this moment of strength.

![]()

Can you feed my cows? Can you feed my goats? Can you make me some bread?

The Idaho fescue also makes for fair to good livestock feed. And, may be easier, more cost-efficient, and most importantly, contributes to healthy soil. They can hold the soil, preventing erosion. Cost-efficient because they are perennial and will use less water. They are also drought resistant.

![]()

When we measure the height of plants - why do we not include their root structures?

Out of my own curiosity, I found a hidden bunch of Idaho fescue and gently moved away the soil to reach the roots. Once I had a solid hold, I tugged, pulled, tripped over myself, and freed it from the ground. Here is what I observed:

![]()

They grow without rhizomes. The roots were scraggly and thick, about 6-8 inches in length. There were tiny hairs all along each thick root. So many individuals coming together with their roots weaving in and out creating a knotted ball of hair.

What a curious sight to see what is under my feet all along. Taking a pause during the quiet of winter led me to the bunchgrass, to the Idaho fescue. And, I’m so thankful it did.

I walk while the sun sets behind the rim. I walk towards the playa, each step less hesitant than the last. I hear the mud crack and crunch beneath my feet, still frozen from the cold night. As I take a large step down into the sea of sagebrush I hear a thump. Was it a coyote I startled?

My fingertips graze the tall grasses. They have a weight to them. As I brush past with my hand, I can feel them pushing back. There is a strength in these grasses that keeps them upright. Standing tall through 80 mph katabatic winds, drought, herds of mule deer, and the rare outsider, like myself who has come to understand them. I want to partner with these grasses. Have them tell me their story and why they stay. How many lives have they watched begin and end here in the playa?

The plant I am particularly drawn to is the bunchgrass, Idaho fescue. It has a heavy top when dried, conspicuous and sturdy. When I hold the seeds in my hands they are smooth, sand-colored; some are bleached white from the sun. The long stem is hollow, but forgiving. It bends with the wind, allowing the katabatic to march a strong whiplash right on through.

And, this katabatic wind. It is not your average wind. It’s pulled through the playa. Creeping up the otherside of the rim, climbing higher and higher. When it reaches the top about to spill over, that's when you run and hide. The katabatic is flung into the desert heat below so fast it can reach speeds of 100 mph. How do these bunchgrasses stand the constant winds blowing them in a downward bend? I can barely stand a 5 minute walk through Chicago with the wind tunnels blowing my hair into a chaotic mess.

For a moment, I felt l was home in Illinois. The tall grasses remind me of a time somewhere deep that is not a part of my present life, but a part of the long ago lives that walked through prairies where buffalo grazed. The flatland here is familiar and comforting. But it’s surrounded with massive reminders of a deep geological past. Had it been yesterday that the Chewaucan River ran over this playa flooding it with 4,000 feet of salty water? When this thought takes over, I turn to the rim and ascend higher to overlook the flatlands of the playa. I close my eyes and imagine sea birds flying about, waves splashing against the face of this cliff, and feel the cool mist of salty air against my cheeks and lips bringing me a taste of my home on the east coast. I’ve made many places a home, but I am here right now looking out at the flatland and home feels far away.

In the suburbs of Chicago, my movements were interrupted by large strip malls, highschools, and highways. There were pockets of open space set aside, divided, and managed where suburbanites like myself could walk manicured paths. I was lucky to live in a neighborhood with many trees and a large pond for swimming and paddling. It was a quiet area, not much happened. Until the fish kills started and I became worried. Shortly after, the algae started to turn turquoise and goopy. It was a noticeable change from the filamentous, dark green plants that would stick in clumps to your paddle.

I have always been consumed by the questions around humans and nature. Why are they treated separately when they are so deeply woven together? In college, my classes enforced scientific classification, but also to think critically and to question everything. I moved to the city of Chicago after graduating with a degree in biology, and a strong love of lakes and ponds.

It wasn’t long for me, I realized I couldn't do city life. But, I wanted to keep my relationship together, so I followed a man to Boston. The relationship ended when the pandemic began. I felt shame for a long time, in letting go of something that we both spent years building. The time was right for us, and I moved to Rhode Island for more school.

There, I cultivated a deeper appreciation for slowness and solitude. I explored places along the coast, went inland to find waterfalls, and climbed down rocky inlets. Many threads began to fray - navigating relationships, school, family illness, covid, multiple jobs became all I was. After graduation, I taught kids bike safety and it was the second best summer of my life. I only left Providence for the waves, realizing that summers in Rhode Island are best spent avoiding the tourist-packed beaches, and finding secret spots inland, along rivers.

I looked outside myself and questioned all the things I thought I wanted, a steady job, a place of my own, a clean apartment, a new car, consumed by the life I've been told I should have. Had I grown used to the standard that work should be turned into income? My energy is income, transferable only by the slide, insert or tap of a credit card. That energy, my energy, is turned into tangible things like my apartment, the clothes on my body, the food in my fridge, the guitar that I dream of each night. The wheel kept spinning, even though it fell off the track. I was not grounded, I was spinning. I was structural, unable to bend like the bunchgrasses do. Just like that, I left. And, I started to bend with the winds that brought change. I was headed to Oregon.

I walk out on the playa to follow the path of bunchgrass. I can see cracks forming in the mud, where water is descending back deeper into the earth feeding the subterranean waterworld. It is a mysterious network of massive underground rivers and ephemeral streams. Do the bunchgrass know this? Is this part of their dependency? Where water runs beneath, is that the path they follow?

The Idaho fescue, this beautiful bunchgrass, has me in a state of captivation. I collect more and take it back to the studio. Somehow I want to embody the movement bunchgrass makes in the wind. How it gently bends all in sync with each other, leaning on its neighbors. I try a few techniques and play with cyanotype printing (see Ann, the Photograph, and Cyan). Tying them in bunches works surprisingly well - who would have guessed? The tops leave a beautiful wave-like pattern across the page and I am pleased. My mind does not want to stop there - what else can these bunchgrasses offer?

Can you make me some paper? Yes, they very much can and they show off their texture in the process. The paper left behind some of their fibers - unable to be sliced into tiny particles by the blender - and I am pleased. Not only by the paper, but by their strength. These fibers are built to withstand katabatic winds. By making paper, I feel I am capturing them in this moment of strength.

Can you feed my cows? Can you feed my goats? Can you make me some bread?

The Idaho fescue also makes for fair to good livestock feed. And, may be easier, more cost-efficient, and most importantly, contributes to healthy soil. They can hold the soil, preventing erosion. Cost-efficient because they are perennial and will use less water. They are also drought resistant.

When we measure the height of plants - why do we not include their root structures?

Out of my own curiosity, I found a hidden bunch of Idaho fescue and gently moved away the soil to reach the roots. Once I had a solid hold, I tugged, pulled, tripped over myself, and freed it from the ground. Here is what I observed:

They grow without rhizomes. The roots were scraggly and thick, about 6-8 inches in length. There were tiny hairs all along each thick root. So many individuals coming together with their roots weaving in and out creating a knotted ball of hair.

What a curious sight to see what is under my feet all along. Taking a pause during the quiet of winter led me to the bunchgrass, to the Idaho fescue. And, I’m so thankful it did.

On alfalfa farming, water, and industrial agriculture

Driving the Oregon Outback Scenic Byway, I pulled over often to observe herds of cattle. Only once, did I get close enough to see their eyes. Really, see them. Close enough to make out their long, coarse eyelashes. See a glint of the sun on their wet eyes, while they stared back. Every time the cattle would pause, consider me for a moment, and then trot slowly away.

One random turn took me up a service road. I kept winding up and up until the snow and ice blocked my path. I turned the car off and walked to the ledge, so I could look out over the basin. There was a stark circle of green in the fields below. It surprised me because this area was at rest, replenishing the soil with snowmelt and rain.

But there it was. A perfectly round, green area of growth. It was alfalfa. How do I know this? I heard it from the farmers.

For the last few years, I’ve been seeking out people who in some way care for the land, air, and water. I want to understand how this relationship is formed, maintained, and at risk to change. Mostly, I want to listen. I want to make space for people to share what challenges they face living on, caring for, and working with land, air, and water. How are people acting in resilience to change? How are they, like bunchgrasses, able to bend with the wind?

I thought a month in Summer Lake would give me plenty of time to talk with people about their relationships with the land, but time flew by faster than a Peregrine falcon. Luckily, through searching and contacting lists of online farm associations, I met a generous couple, Chuck and Susan.

It was my third week in Summer Lake. On a warm day with blue skies, I drove an hour north to Christmas Valley to meet Chuck and Susan. Wearing my favorite dark green, wool sweater, the one with a hole that some hungry moths had worsened recently, I pulled into a cafe. I was 30 minutes early, which is very unlike me. But, I could sit with a coffee and prepare my interview questions for the 100th time. Upon returning to my car, I realized that my keys had stopped working (that’s more like me). I immediately called my father to try and fix the key, taking it apart and putting it back together did not help. My interview was starting soon and I had no way to get there. I called Chuck and explained the situation. His voice, kind and understanding, agreed to meet at the cafe.

Chuck and Susan have known each other since high school and are both 3rd generation farmers in Christmas Valley, Oregon. Sitting across from them, I considered the innocence of young love and the dedication it takes to commit to another person at that age. They are in sync, making space and giving a gentle nudge when they know the other has more to say. I wondered if there was an exact moment in their life when the challenges facing them started to take hold, interrupting the innocence of young love. Whatever it had been, they kept pushing through, achieving safety and security for their livelihood.

In 2016, America became what it always has been - a Great Divide. And, the majority of us still haven’t shown that we can cross it. To bypass all of the divisions, I want to go in and close the gap. To do that, I have to go deeper into the divide, by going in close to reveal the personal, emotional, and interconnectedness between you and me, until there is one. Filling the air with our vibrations at that cafe, I started to feel the threads weave between us. They trusted me with their deepest concerns. Some about Summer Lake’s water, the blood to their livelihood, or the lifeblood. Others, about the younger generation of farmers, including the future of their children.

The problem of alfalfa

On Chuck and Susan’s relationship with the land, we discussed at length their fields of Alfalfa, a green, luscious plant that makes for a great source of protein for livestock. Christmas Valley is hungry for the alfalfa. Because of how cold temperatures are at night, the plants store a lot of energy to survive the frigid and arid climate. These conditions make the alfalfa in Christmas Valley super high in protein. The alfalfa is then fed to livestock. With its high protein, it makes a great food source for the cattle. Chuck asked me, “have you ever heard of Tillamook Cheese? You’re probably eating some of our product.” He told me that the dairy cows in Tillamook, Oregon are fed their alfalfa. The cheese is produced and sold all over the US. Susan explained her friend found Tillamook Cheese in New York City going for 20$ a block. Their alfalfa travels from Christmas Valley to elsewhere across Oregon, California, Washington, and even across the sea to Asia. When all is considered, this market is well over a million dollar industry.

Chuck shares his concerns on foreign investment in US agricultural land, and there was a moment where I could feel tension building in his voice. Chuck says, “we’ve started to notice that they are starting to buy here.” The alfalfa industry in Oregon relies on foreign buyers to cover freight, an expensive cost. If buyers start to own land, alfalfa farmers in Christmas Valley will lose customers.

According to the USDA, foreign investors can purchase US agricultural land. The Agricultural Foreign Investment Disclosure Act (1978) established a nationwide system for collecting and reporting information on foreign investors who acquire, transfer, or hold interest in US agricultural land. In the most recent published report (2021), approximately 40 million acres of US agricultural land is privately owned by foreign investors. That’s 3.1% of all privately held agricultural land and 1.8% of all land in the US. The leading foreign investor is Canada (31%), followed by Netherlands (12%), Italy (7%), UK (6%), and Germany (6%). For Christmas Valley’s county, there are 9,328 acres owned by Canada.

While I heard Chuck’s concerns as legitimate, it does seem that Oregon has strict restrictions on foreign investors in purchasing and owning agricultural land. As a cautionary tale, this concern may stem from an agenda prompting fear of the other. Not at the hands of my acquaintance Chuck, but by the greater forces that are surrounding him in provoking fear of foreign investors coming in to take US land and starve americans. And since his buyers are not in the list of top investors, nor hold land in Oregon, I am relieved for Chuck, Susan, and their children, who one day they hope will take on the family farm, and all the challenges that come with it.

But, the greater concern lies just before foreign buyers. It is that food is exported. It is that the centralized control of all prices and standards in the international food economy puts the control in the hands of the corporations. As Wendell Berry describes, these procedures (aka the “free market") have been imposed on farmers by force or seduction into dependence on the industrial economy, “robbing people of their property and labor.” Robbing people of their independence and of choice.

One of those choices is choosing capital over the land. The pressure to make capital, “becomes a competition in land exploitation”. This choice leads to the use of toxic chemicals, expensive labor, machines, and fuel. Chuck’s family came to Christmas Valley in 1977 to begin alfalfa farming. His family was in logging prior to that. Though it is a family farm, it operates like a large agribusiness farm. There are 3000 acres in “production”, and 400 are for grain crops. Chuck explains, “we’re growing primarily alfalfa hay. We also grow rotational crops (including) oats, barley, but we’re after the alfalfa. It’s the highest protein source for beef, sheep, horses, and goats.” I interrupt and ask if they are growing food for people. Without skipping a beat, Chuck replies, “Ah, alfalfa sprouts? We don’t produce that product, we produce the product that feeds the animals. (It is) shipped all over Asia, Oregon, Washington, and California. Every 6-7 years you have to rotate crops. If you don’t, it quits producing; 1-2 years with the oats, trinical, barley, and wheat. It depends on the market for grain hay, if it’s low. You don’t make near the amount of money per acre (compared) to alfalfa.”

I would guess that Chuck and I disagree on the principle of a free market. I’d use him as an example, but I don’t want to invalidate the very grounds he has built a livelihood on. I also don’t want to assume that he is making this choice. He has been pulled into the agribusiness model. Choices aren’t driven by the land, they are choices driven by market prices. If given better choices for food production, would he choose that path? The path of the small farm, love, and practices of care?

Rather than pursuing an argument, I have other ways to bridge this gap. I listen for the emotional and personal. I carefully feel the rhythm of their responses, and notice when something is tugging, when something is stuck. “You might be doing fine this year, and two years down the road you don’t know…” This is why I don’t argue. While life is resilient, it is also fragile. And, I don’t know what someone has gone through just to make it out the door.

Though Chuck is a humble man, he is very proud of being a farmer. “It’s high stress. So, I sleep in the field in the summertime.” It tires him, but he is committed to the work. In doing so, he has created an intimate connection with the growth cycles of alfalfa. Chuck starts to explain to me what an alfalfa harvest is like. “I have to stay there and wait for the dew to come in. Wait for the night time moisture to come in… I have the crew on standby and call them in.” To operate this harvest, Chuck runs the farm on automation. He hires 16 people to work the machines over the hot, dry summer months. During harvest, some days are 20 hours long. Susan nods her head, “it’s not just a 9-5 job.”

Chuck brought up his concerns about the decline in farm labor. Susan added, “the hours are too long and it’s too demanding.” Compounded with the decline in the number of farms and an increase in average farm size, working conditions will worsen. The centralization of agriculture to the large farm doesn’t make things easier in terms of labor. Rather than sharing the work amongst many, the labor is forced by machines to be hyperactive for a short period of time. These machines follow a time frame differently than a human. They can turn on and off with good maintenance and a turn of a key. They don’t require sleep. There is no rhythmic pulse, with blood that circulates through the veins and arteries, making a continual return to the heart. Humans follow a much slower time frame. What will it take for industrial agriculture to dissociate from its name, and slow down?

Industrial agriculture is suffering from vertigo. Vertigo is a real thing, caused by the world speeding up around us. It is felt differently, and it is shared. Humans are tired, exhausted from the 24/7 drip of irrigation, whir of tumbling bales, and thinking of when the 10-year drought will end.

Chuck turned serious on the topic of water availability, “we need the rain at the right time.” Not only do they need it at the right time, but they urgently need it now. West of Christmas Valley is Klamath Falls, where in 2021 a historic water shut-off occurred in the basin. Farmers struggled to find other ways to survive. Many used groundwater wells. The future is unknown, spurring conflict between Klamath basin farmers, wildlife ecologists, and tribes located downstream.

“The reason is their water table is dropping… drastically.” Chuck explained to me why they aren’t as concerned about a shut down, “we have about 100 years of water if we continue with the drought that we’re in.” He avoids calling it climate change. Our perception of the term climate change differs, but also overlaps. It describes a serious dilemma that we all experience differently, and share in. Chuck is focused on his own truths related to the changing climate, formed by lived experience. “Things are cyclical and will go up and down… and, they have in the past.” He says, shrugging his shoulders. There is a tinge of denial, but is it harmful? Or is it just a way to cope and hold on to hope? That things will balance themselves out.

To cure industrial agriculture’s vertigo, it must seek balance. What do you do to level out a fast-paced system? Sleep. Slowing down the forces that be. A practice involving sleep and a circulation of care. A reciprocal practice will rejuvenate the rhythmic pulse that passes through humans to land, to water, to fungi, to microorganism, to plant, to air, again, again, and again.

Chuck is marginally getting closer to a slow paced practice. They work with the irrigation and electric company, placing the water closer to the ground so there is less evaporation. He also doesn’t seem interested in acquiring any more acres.

Nonetheless, his progress is hindered by a reliance on the suppliers. “We’re working both with the irrigation company and electric company. They have programs to assist us in putting in packages that are more economical. Putting that water lower to the ground so we’re not getting that evaporation.” This is how Chuck is saving money and water, but it leads to other problems. If the water drags too slow on the ground, it causes erosion. The land in the high desert is highly erodible. The rolling hills only speed up the erosion, spilling into large cracks and washing the nutrients away.

Hills are tricky in farming. “Nice and flat, you don’t have erosion,” is how Chuck phrases it. From another perspective, hills can be your friend. It just takes a pause, and to adapt your practice. From my observation, the hills in their fields weren’t that large. If the hill was left with bunchgrass and sagebrush, both plants would do well in holding the soil. Sagebrush can reach up to 15 feet deep; and bunchgrass is drought resistant, with a thick, tangled root ball. When I asked if this was a method they would consider, it was rejected. Not by Chuck’s own personal choice, but by his international customers. “Korea, China, Japan pay the freight cost (which) gets pretty expensive. So, they don’t want to buy a product that’s not pure. They don’t like dirt, no weeds.”

I can’t help but hang on to that word, “dirt”. The potential of dirt is soil. Healthy soil. If Chuck shifted from international buyers to local buyers, shrinking his operation, the potential of the dirt could be restored. In all the efforts of growing alfalfa, there are numerous challenges. These challenges are all wound up in the complexities of industrial agriculture. The buyers, who control the quality of the product. The suppliers, who control the availability of energy and water. And then, the growers. What control do they have left? What freedoms do they have in deciding what they grow, and how they grow it?

Driving the Oregon Outback Scenic Byway, I pulled over often to observe herds of cattle. Only once, did I get close enough to see their eyes. Really, see them. Close enough to make out their long, coarse eyelashes. See a glint of the sun on their wet eyes, while they stared back. Every time the cattle would pause, consider me for a moment, and then trot slowly away.

One random turn took me up a service road. I kept winding up and up until the snow and ice blocked my path. I turned the car off and walked to the ledge, so I could look out over the basin. There was a stark circle of green in the fields below. It surprised me because this area was at rest, replenishing the soil with snowmelt and rain.

But there it was. A perfectly round, green area of growth. It was alfalfa. How do I know this? I heard it from the farmers.

For the last few years, I’ve been seeking out people who in some way care for the land, air, and water. I want to understand how this relationship is formed, maintained, and at risk to change. Mostly, I want to listen. I want to make space for people to share what challenges they face living on, caring for, and working with land, air, and water. How are people acting in resilience to change? How are they, like bunchgrasses, able to bend with the wind?

I thought a month in Summer Lake would give me plenty of time to talk with people about their relationships with the land, but time flew by faster than a Peregrine falcon. Luckily, through searching and contacting lists of online farm associations, I met a generous couple, Chuck and Susan.

It was my third week in Summer Lake. On a warm day with blue skies, I drove an hour north to Christmas Valley to meet Chuck and Susan. Wearing my favorite dark green, wool sweater, the one with a hole that some hungry moths had worsened recently, I pulled into a cafe. I was 30 minutes early, which is very unlike me. But, I could sit with a coffee and prepare my interview questions for the 100th time. Upon returning to my car, I realized that my keys had stopped working (that’s more like me). I immediately called my father to try and fix the key, taking it apart and putting it back together did not help. My interview was starting soon and I had no way to get there. I called Chuck and explained the situation. His voice, kind and understanding, agreed to meet at the cafe.

Chuck and Susan have known each other since high school and are both 3rd generation farmers in Christmas Valley, Oregon. Sitting across from them, I considered the innocence of young love and the dedication it takes to commit to another person at that age. They are in sync, making space and giving a gentle nudge when they know the other has more to say. I wondered if there was an exact moment in their life when the challenges facing them started to take hold, interrupting the innocence of young love. Whatever it had been, they kept pushing through, achieving safety and security for their livelihood.

In 2016, America became what it always has been - a Great Divide. And, the majority of us still haven’t shown that we can cross it. To bypass all of the divisions, I want to go in and close the gap. To do that, I have to go deeper into the divide, by going in close to reveal the personal, emotional, and interconnectedness between you and me, until there is one. Filling the air with our vibrations at that cafe, I started to feel the threads weave between us. They trusted me with their deepest concerns. Some about Summer Lake’s water, the blood to their livelihood, or the lifeblood. Others, about the younger generation of farmers, including the future of their children.

The problem of alfalfa

On Chuck and Susan’s relationship with the land, we discussed at length their fields of Alfalfa, a green, luscious plant that makes for a great source of protein for livestock. Christmas Valley is hungry for the alfalfa. Because of how cold temperatures are at night, the plants store a lot of energy to survive the frigid and arid climate. These conditions make the alfalfa in Christmas Valley super high in protein. The alfalfa is then fed to livestock. With its high protein, it makes a great food source for the cattle. Chuck asked me, “have you ever heard of Tillamook Cheese? You’re probably eating some of our product.” He told me that the dairy cows in Tillamook, Oregon are fed their alfalfa. The cheese is produced and sold all over the US. Susan explained her friend found Tillamook Cheese in New York City going for 20$ a block. Their alfalfa travels from Christmas Valley to elsewhere across Oregon, California, Washington, and even across the sea to Asia. When all is considered, this market is well over a million dollar industry.

Chuck shares his concerns on foreign investment in US agricultural land, and there was a moment where I could feel tension building in his voice. Chuck says, “we’ve started to notice that they are starting to buy here.” The alfalfa industry in Oregon relies on foreign buyers to cover freight, an expensive cost. If buyers start to own land, alfalfa farmers in Christmas Valley will lose customers.

According to the USDA, foreign investors can purchase US agricultural land. The Agricultural Foreign Investment Disclosure Act (1978) established a nationwide system for collecting and reporting information on foreign investors who acquire, transfer, or hold interest in US agricultural land. In the most recent published report (2021), approximately 40 million acres of US agricultural land is privately owned by foreign investors. That’s 3.1% of all privately held agricultural land and 1.8% of all land in the US. The leading foreign investor is Canada (31%), followed by Netherlands (12%), Italy (7%), UK (6%), and Germany (6%). For Christmas Valley’s county, there are 9,328 acres owned by Canada.

While I heard Chuck’s concerns as legitimate, it does seem that Oregon has strict restrictions on foreign investors in purchasing and owning agricultural land. As a cautionary tale, this concern may stem from an agenda prompting fear of the other. Not at the hands of my acquaintance Chuck, but by the greater forces that are surrounding him in provoking fear of foreign investors coming in to take US land and starve americans. And since his buyers are not in the list of top investors, nor hold land in Oregon, I am relieved for Chuck, Susan, and their children, who one day they hope will take on the family farm, and all the challenges that come with it.

But, the greater concern lies just before foreign buyers. It is that food is exported. It is that the centralized control of all prices and standards in the international food economy puts the control in the hands of the corporations. As Wendell Berry describes, these procedures (aka the “free market") have been imposed on farmers by force or seduction into dependence on the industrial economy, “robbing people of their property and labor.” Robbing people of their independence and of choice.

One of those choices is choosing capital over the land. The pressure to make capital, “becomes a competition in land exploitation”. This choice leads to the use of toxic chemicals, expensive labor, machines, and fuel. Chuck’s family came to Christmas Valley in 1977 to begin alfalfa farming. His family was in logging prior to that. Though it is a family farm, it operates like a large agribusiness farm. There are 3000 acres in “production”, and 400 are for grain crops. Chuck explains, “we’re growing primarily alfalfa hay. We also grow rotational crops (including) oats, barley, but we’re after the alfalfa. It’s the highest protein source for beef, sheep, horses, and goats.” I interrupt and ask if they are growing food for people. Without skipping a beat, Chuck replies, “Ah, alfalfa sprouts? We don’t produce that product, we produce the product that feeds the animals. (It is) shipped all over Asia, Oregon, Washington, and California. Every 6-7 years you have to rotate crops. If you don’t, it quits producing; 1-2 years with the oats, trinical, barley, and wheat. It depends on the market for grain hay, if it’s low. You don’t make near the amount of money per acre (compared) to alfalfa.”

I would guess that Chuck and I disagree on the principle of a free market. I’d use him as an example, but I don’t want to invalidate the very grounds he has built a livelihood on. I also don’t want to assume that he is making this choice. He has been pulled into the agribusiness model. Choices aren’t driven by the land, they are choices driven by market prices. If given better choices for food production, would he choose that path? The path of the small farm, love, and practices of care?

Rather than pursuing an argument, I have other ways to bridge this gap. I listen for the emotional and personal. I carefully feel the rhythm of their responses, and notice when something is tugging, when something is stuck. “You might be doing fine this year, and two years down the road you don’t know…” This is why I don’t argue. While life is resilient, it is also fragile. And, I don’t know what someone has gone through just to make it out the door.

Though Chuck is a humble man, he is very proud of being a farmer. “It’s high stress. So, I sleep in the field in the summertime.” It tires him, but he is committed to the work. In doing so, he has created an intimate connection with the growth cycles of alfalfa. Chuck starts to explain to me what an alfalfa harvest is like. “I have to stay there and wait for the dew to come in. Wait for the night time moisture to come in… I have the crew on standby and call them in.” To operate this harvest, Chuck runs the farm on automation. He hires 16 people to work the machines over the hot, dry summer months. During harvest, some days are 20 hours long. Susan nods her head, “it’s not just a 9-5 job.”

Chuck brought up his concerns about the decline in farm labor. Susan added, “the hours are too long and it’s too demanding.” Compounded with the decline in the number of farms and an increase in average farm size, working conditions will worsen. The centralization of agriculture to the large farm doesn’t make things easier in terms of labor. Rather than sharing the work amongst many, the labor is forced by machines to be hyperactive for a short period of time. These machines follow a time frame differently than a human. They can turn on and off with good maintenance and a turn of a key. They don’t require sleep. There is no rhythmic pulse, with blood that circulates through the veins and arteries, making a continual return to the heart. Humans follow a much slower time frame. What will it take for industrial agriculture to dissociate from its name, and slow down?

Industrial agriculture is suffering from vertigo. Vertigo is a real thing, caused by the world speeding up around us. It is felt differently, and it is shared. Humans are tired, exhausted from the 24/7 drip of irrigation, whir of tumbling bales, and thinking of when the 10-year drought will end.

Chuck turned serious on the topic of water availability, “we need the rain at the right time.” Not only do they need it at the right time, but they urgently need it now. West of Christmas Valley is Klamath Falls, where in 2021 a historic water shut-off occurred in the basin. Farmers struggled to find other ways to survive. Many used groundwater wells. The future is unknown, spurring conflict between Klamath basin farmers, wildlife ecologists, and tribes located downstream.

“The reason is their water table is dropping… drastically.” Chuck explained to me why they aren’t as concerned about a shut down, “we have about 100 years of water if we continue with the drought that we’re in.” He avoids calling it climate change. Our perception of the term climate change differs, but also overlaps. It describes a serious dilemma that we all experience differently, and share in. Chuck is focused on his own truths related to the changing climate, formed by lived experience. “Things are cyclical and will go up and down… and, they have in the past.” He says, shrugging his shoulders. There is a tinge of denial, but is it harmful? Or is it just a way to cope and hold on to hope? That things will balance themselves out.

To cure industrial agriculture’s vertigo, it must seek balance. What do you do to level out a fast-paced system? Sleep. Slowing down the forces that be. A practice involving sleep and a circulation of care. A reciprocal practice will rejuvenate the rhythmic pulse that passes through humans to land, to water, to fungi, to microorganism, to plant, to air, again, again, and again.

Chuck is marginally getting closer to a slow paced practice. They work with the irrigation and electric company, placing the water closer to the ground so there is less evaporation. He also doesn’t seem interested in acquiring any more acres.

Nonetheless, his progress is hindered by a reliance on the suppliers. “We’re working both with the irrigation company and electric company. They have programs to assist us in putting in packages that are more economical. Putting that water lower to the ground so we’re not getting that evaporation.” This is how Chuck is saving money and water, but it leads to other problems. If the water drags too slow on the ground, it causes erosion. The land in the high desert is highly erodible. The rolling hills only speed up the erosion, spilling into large cracks and washing the nutrients away.

Hills are tricky in farming. “Nice and flat, you don’t have erosion,” is how Chuck phrases it. From another perspective, hills can be your friend. It just takes a pause, and to adapt your practice. From my observation, the hills in their fields weren’t that large. If the hill was left with bunchgrass and sagebrush, both plants would do well in holding the soil. Sagebrush can reach up to 15 feet deep; and bunchgrass is drought resistant, with a thick, tangled root ball. When I asked if this was a method they would consider, it was rejected. Not by Chuck’s own personal choice, but by his international customers. “Korea, China, Japan pay the freight cost (which) gets pretty expensive. So, they don’t want to buy a product that’s not pure. They don’t like dirt, no weeds.”

I can’t help but hang on to that word, “dirt”. The potential of dirt is soil. Healthy soil. If Chuck shifted from international buyers to local buyers, shrinking his operation, the potential of the dirt could be restored. In all the efforts of growing alfalfa, there are numerous challenges. These challenges are all wound up in the complexities of industrial agriculture. The buyers, who control the quality of the product. The suppliers, who control the availability of energy and water. And then, the growers. What control do they have left? What freedoms do they have in deciding what they grow, and how they grow it?

On a small farm

A week after sitting in the cafe with Chuck and Susan, I stayed on a small farm in Southwest, Oregon. A friend offered to host me for a night. Here is the shortlist of what I observed: friends in muck boots, lambs, a clear water river with a million multi-colored smooth rocks, dairy cows, fig trees, raspberries, hills covered in a diverse patchwork of plants, blackberries, walls built from clay and hay, chickens, a black widow, ponds, and a few homes for farm workers to live. We talked about rivers, water rights, irrigation, farmers markets, barn owls, love, and about the words, water is life. Small farm, big miracles.

![]()

I arrived at night, when the atmosphere was still. The moonlight shone bright off distant bodies of water when I pulled onto the farm. A kind human from Wisconsin greeted me past the gate, with a giant fluffy Great Pyrenees, Moony, at his side. As I started to pull forward and park, Moony blocked my way, looking at me with droopy, loving eyes. Moony became my best friend there, and was about to come home with me if only I had a bigger car. I still think about him.

![]()

I walked into Nathan and Ellen’s home. It is a restored barn, adorned with their many keepsakes from all over the southwest and the Navajo Nation. Ellen greeted me with a warm smile and firm handshake. Immediately, she offered me a cup of hot tea with honey made from their bees. The tea was full of health benefits, nettle to soothe aches, pains, and lower blood pressure. Sensing things were busy, I offered my assistance - please put me to work. Ellen instead wanted to show me my sleeping quarters, out in the “horse stables”.

The “horse stables” were small apartments, and/or work spaces. Ellen opened the heavy wooden door to my room. It was a small loft space, with a window that looked out another old barn. “You’ll find the bathroom out this way, but if you just have to pee at night, feel free to squat right outside the door,” as she pointed down the driveway. I thanked Ellen, and she returned to prepping dinner, helping her son with homework, and finishing up a few lingering tasks, including checking on the burst pipes. It rarely drops below freezing in their valley, but last night plummeted to 11 degrees fahrenheit. This was a big issue for them, because they have several tenants on their farm paying for rent, water, and some, electricity.

For a short bit, I settled in my room. There was a desk, a bed, and a window that looked out into the old barn where the barn owls screech at night. I returned to the main house, where Nathan and Ellen were making dinner. I smelled the sizzle of salmon, garlic, and lemon. Looking at the spread, every color of the rainbow was there. Homegrown squash, the color of a sunset, salad greens from the garden, shiitake mushrooms, and purple potatoes were waiting to be plated. The warmth and subtle smell of smoke from the wood stove tied the room together.

The four of us sat comfortably cross-legged around the table. I had three cups of tea that night. Ellen just kept refilling my cup, until I had to throw myself over the table. I felt sleep creeping up and down my eyelids, as I looked over at Ellen leaning back on the couch. Before that could happen I went out with Nathan to check the water pipe. He gave me a tour, introducing me to the chickens. He walked with purpose while he shared the history of the farm. He described how it used to be a horse farm, and they raced the horses around the 3 acres. All the stables have been since rennovated into a sauna, or small apartments for farmers and teachers.

![]()

Nathan has a deep love for this place. As he described to me the way water from the pumps fill the ponds to be used for irrigation, I could hear his voice get a tad bit louder and faster. Without having to say it directly, he is proud of what he’s built here.

![]()

Opening the stable with the waterpipe, we check to make sure his rig has held up. The super glue and a plastic cap did the trick. We turn the pipe back on which is inside a ground covered box. “Now, there’s something I really want you to see, but we have to be careful,” Nathan motions to the lid. When we lift the cover, he points to the location where a black widow is hiding. I peek my head under and sure enough there it is. Marked by the bold, red hourglass. All creatures have a place here.

![]()

The next morning, Ellen and I talked over coffee, eggs, and lamb seasoned with coriander, fennel, and other mouthwatering spices straight from the garden. When I mentioned the beautiful sunrise over the mountains, she glanced and smiled. But, eyes squinting, she pointed out the “chemtrails”. While I’m a skeptic, I also have an open mind. Listening, she explained that these chemtrails are supposed to increase rain in the area, which is experiencing a long drought. I brought up a recent book I read by Wendell Berry, The Unsettling of America. In it, Berry presents a map of a future farm in America drawn by Davis Meltzer for National Geographic. In the image, there are greenhouses, water pumps, vertical farms, crop dusters, plastic domes, and weather reporting machines. The “farms will be larger, with fewer trees, hedges, and roadways.” Even the weather will be controlled, and “tame a hailstorm and tornado dangers” with “atomic energy”. I will never forget Ellen’s response. “Oh, truth-chills,” as she touched her arm.

“Okay, so who’s next?” Ellen was asking the goats. After coffee and breakfast, Ellen brought me out with her to milk the goats. This intimate event happens every morning.

“Nona!” She greets them each by name as they hop up to the table.

“That’s Tia.”

“Hi, Tia.” I scratch her head.

We’re hoping she’s pregnant.”

![]()

I look at her bright green and yellow eyes for a moment. She looks so young. I was surprised to find out Tia was a grandmother!

There is a different feeling in the air with Tia and Nona. There is more space for love, when fear is absent. They have never known or seen violence. They move where they please and are fed nutritious seaweed Ellen harvests herself from the Oregon coast. The rest of the goats inch closer to scratch their head up against my wool sweater, leaving coarse hairs behind. I’m honored by the affection.

I carefully step around a lot of goat poop. It will head to compost where it will be spread on the fields, feeding the soil, the worms, and the plants. Everything here fits into a circular motion of care. What goes in, comes back around, again, again, and again. I can feel my pulse changing as it syncs up with the vibrant life around me.

![]()

These days when I can’t quite finish a yawn and I’m short of breath, I search for that rhythmic pulse. I’ll go outside, find the nearest plant and just hold it in my hands. That small act brings me peace, making me feel grounded and connected to something bigger than myself. Being at the small farm with Ellen and Nathan was the balance I needed to feel before driving back to Rhode Island, where most of my life is still unknown. There are threads not quite sewn into place. It makes me nervous, but I’m also excited that I have left space for cultivating balance. A space for rest, space for vibrancy, and space for creativity.

Seeing how much creativity Nathan and Ellen brought to their farm makes me want to share with Chuck. I want to show him the potential for freedom on a small farm and when you act locally. When you get big, you start to build a reliance on the systems (suppliers) that “helped” you get there. It’s the problem of scale. Chuck and I discussed how tries to strike a balance between making a profit and staying within his limits. I cannot fault him for that. But, what about the limits of the land? I’m afraid it’s reaching a critical point for Chuck. From our talk, erosion and large cracks in the ground are signs that the land has reached its limit. When I hear bigger is better, I can’t help but cringe.

How many times have you heard less is more, and let out a sigh of relief? What would Chuck and Susan think if we took a walk together on Nathan and Ellen’s farm? Would they see what I see? What are their perceptions of the land they work on? To understand this I had Chuck sketch a mental map of the watershed. Since he spends most of his time on the farm, he drew the alfalfa fields. Standing in the fields were figures representing a coyote, jackrabbit, and other wildlife.

![]()

I interpret his map. He recognizes that he is not the only one depending on the land. The coyote, jackrabbit, and plants are just as much a part of the watershed as he is. I left the interview with Chuck and Susan hoping that this mental map was more of a process for reflection. I left hoping that they will slow down, and see themselves as part of something bigger. And I don’t mean the big farm, I mean the big task at hand. To be a participant in circular motions of care, feel the rhythmic pulse, and be a part of curing our vertigo.

![]()

I hear the sentiment that America needs to open its eyes to the injustices, inequities, and horrific hate crimes that occur deep within the systems set up to protect us... Agriculture in the US was set up to protect us, ensuring food was available to all. We are here today knowing that is not the case - food pantries, food assistance programs, food deserts, do I need to continue? America needs to close its eyes - rest. In times of rest, we become aware and accept, we let go. In doing that, maybe together we can gently restore the roots of farming that US industrial agriculture has destroyed.

![]()

A tree that grows slow, does so to ensure it will live a long, healthy life. Be like a tree. Grow slow. Close your eyes - rest.

![]()

A week after sitting in the cafe with Chuck and Susan, I stayed on a small farm in Southwest, Oregon. A friend offered to host me for a night. Here is the shortlist of what I observed: friends in muck boots, lambs, a clear water river with a million multi-colored smooth rocks, dairy cows, fig trees, raspberries, hills covered in a diverse patchwork of plants, blackberries, walls built from clay and hay, chickens, a black widow, ponds, and a few homes for farm workers to live. We talked about rivers, water rights, irrigation, farmers markets, barn owls, love, and about the words, water is life. Small farm, big miracles.

I arrived at night, when the atmosphere was still. The moonlight shone bright off distant bodies of water when I pulled onto the farm. A kind human from Wisconsin greeted me past the gate, with a giant fluffy Great Pyrenees, Moony, at his side. As I started to pull forward and park, Moony blocked my way, looking at me with droopy, loving eyes. Moony became my best friend there, and was about to come home with me if only I had a bigger car. I still think about him.

I walked into Nathan and Ellen’s home. It is a restored barn, adorned with their many keepsakes from all over the southwest and the Navajo Nation. Ellen greeted me with a warm smile and firm handshake. Immediately, she offered me a cup of hot tea with honey made from their bees. The tea was full of health benefits, nettle to soothe aches, pains, and lower blood pressure. Sensing things were busy, I offered my assistance - please put me to work. Ellen instead wanted to show me my sleeping quarters, out in the “horse stables”.

The “horse stables” were small apartments, and/or work spaces. Ellen opened the heavy wooden door to my room. It was a small loft space, with a window that looked out another old barn. “You’ll find the bathroom out this way, but if you just have to pee at night, feel free to squat right outside the door,” as she pointed down the driveway. I thanked Ellen, and she returned to prepping dinner, helping her son with homework, and finishing up a few lingering tasks, including checking on the burst pipes. It rarely drops below freezing in their valley, but last night plummeted to 11 degrees fahrenheit. This was a big issue for them, because they have several tenants on their farm paying for rent, water, and some, electricity.

For a short bit, I settled in my room. There was a desk, a bed, and a window that looked out into the old barn where the barn owls screech at night. I returned to the main house, where Nathan and Ellen were making dinner. I smelled the sizzle of salmon, garlic, and lemon. Looking at the spread, every color of the rainbow was there. Homegrown squash, the color of a sunset, salad greens from the garden, shiitake mushrooms, and purple potatoes were waiting to be plated. The warmth and subtle smell of smoke from the wood stove tied the room together.

The four of us sat comfortably cross-legged around the table. I had three cups of tea that night. Ellen just kept refilling my cup, until I had to throw myself over the table. I felt sleep creeping up and down my eyelids, as I looked over at Ellen leaning back on the couch. Before that could happen I went out with Nathan to check the water pipe. He gave me a tour, introducing me to the chickens. He walked with purpose while he shared the history of the farm. He described how it used to be a horse farm, and they raced the horses around the 3 acres. All the stables have been since rennovated into a sauna, or small apartments for farmers and teachers.

Nathan has a deep love for this place. As he described to me the way water from the pumps fill the ponds to be used for irrigation, I could hear his voice get a tad bit louder and faster. Without having to say it directly, he is proud of what he’s built here.

Opening the stable with the waterpipe, we check to make sure his rig has held up. The super glue and a plastic cap did the trick. We turn the pipe back on which is inside a ground covered box. “Now, there’s something I really want you to see, but we have to be careful,” Nathan motions to the lid. When we lift the cover, he points to the location where a black widow is hiding. I peek my head under and sure enough there it is. Marked by the bold, red hourglass. All creatures have a place here.

The next morning, Ellen and I talked over coffee, eggs, and lamb seasoned with coriander, fennel, and other mouthwatering spices straight from the garden. When I mentioned the beautiful sunrise over the mountains, she glanced and smiled. But, eyes squinting, she pointed out the “chemtrails”. While I’m a skeptic, I also have an open mind. Listening, she explained that these chemtrails are supposed to increase rain in the area, which is experiencing a long drought. I brought up a recent book I read by Wendell Berry, The Unsettling of America. In it, Berry presents a map of a future farm in America drawn by Davis Meltzer for National Geographic. In the image, there are greenhouses, water pumps, vertical farms, crop dusters, plastic domes, and weather reporting machines. The “farms will be larger, with fewer trees, hedges, and roadways.” Even the weather will be controlled, and “tame a hailstorm and tornado dangers” with “atomic energy”. I will never forget Ellen’s response. “Oh, truth-chills,” as she touched her arm.

“Okay, so who’s next?” Ellen was asking the goats. After coffee and breakfast, Ellen brought me out with her to milk the goats. This intimate event happens every morning.

“Nona!” She greets them each by name as they hop up to the table.

“That’s Tia.”

“Hi, Tia.” I scratch her head.

We’re hoping she’s pregnant.”

I look at her bright green and yellow eyes for a moment. She looks so young. I was surprised to find out Tia was a grandmother!

There is a different feeling in the air with Tia and Nona. There is more space for love, when fear is absent. They have never known or seen violence. They move where they please and are fed nutritious seaweed Ellen harvests herself from the Oregon coast. The rest of the goats inch closer to scratch their head up against my wool sweater, leaving coarse hairs behind. I’m honored by the affection.

I carefully step around a lot of goat poop. It will head to compost where it will be spread on the fields, feeding the soil, the worms, and the plants. Everything here fits into a circular motion of care. What goes in, comes back around, again, again, and again. I can feel my pulse changing as it syncs up with the vibrant life around me.

These days when I can’t quite finish a yawn and I’m short of breath, I search for that rhythmic pulse. I’ll go outside, find the nearest plant and just hold it in my hands. That small act brings me peace, making me feel grounded and connected to something bigger than myself. Being at the small farm with Ellen and Nathan was the balance I needed to feel before driving back to Rhode Island, where most of my life is still unknown. There are threads not quite sewn into place. It makes me nervous, but I’m also excited that I have left space for cultivating balance. A space for rest, space for vibrancy, and space for creativity.

Seeing how much creativity Nathan and Ellen brought to their farm makes me want to share with Chuck. I want to show him the potential for freedom on a small farm and when you act locally. When you get big, you start to build a reliance on the systems (suppliers) that “helped” you get there. It’s the problem of scale. Chuck and I discussed how tries to strike a balance between making a profit and staying within his limits. I cannot fault him for that. But, what about the limits of the land? I’m afraid it’s reaching a critical point for Chuck. From our talk, erosion and large cracks in the ground are signs that the land has reached its limit. When I hear bigger is better, I can’t help but cringe.

How many times have you heard less is more, and let out a sigh of relief? What would Chuck and Susan think if we took a walk together on Nathan and Ellen’s farm? Would they see what I see? What are their perceptions of the land they work on? To understand this I had Chuck sketch a mental map of the watershed. Since he spends most of his time on the farm, he drew the alfalfa fields. Standing in the fields were figures representing a coyote, jackrabbit, and other wildlife.

I interpret his map. He recognizes that he is not the only one depending on the land. The coyote, jackrabbit, and plants are just as much a part of the watershed as he is. I left the interview with Chuck and Susan hoping that this mental map was more of a process for reflection. I left hoping that they will slow down, and see themselves as part of something bigger. And I don’t mean the big farm, I mean the big task at hand. To be a participant in circular motions of care, feel the rhythmic pulse, and be a part of curing our vertigo.

I hear the sentiment that America needs to open its eyes to the injustices, inequities, and horrific hate crimes that occur deep within the systems set up to protect us... Agriculture in the US was set up to protect us, ensuring food was available to all. We are here today knowing that is not the case - food pantries, food assistance programs, food deserts, do I need to continue? America needs to close its eyes - rest. In times of rest, we become aware and accept, we let go. In doing that, maybe together we can gently restore the roots of farming that US industrial agriculture has destroyed.

A tree that grows slow, does so to ensure it will live a long, healthy life. Be like a tree. Grow slow. Close your eyes - rest.